Input Devices

Have you:

[x] Described your design and fabrication process using words/images/screenshots.

[x] Explained the programming process/es you used and how the microcontroller datasheet helped you.

[x] Explained problems and how you fixed them

[x] Included original design files and code

Sensing temperature and humidity with the DHT-11 - 2021

The fabrication of these boards is covered in Electronics Design:

The goal for this assignment is to sense temperature and humidity with the DHT-11 using the ATTiny44. I am doing this following my work in output devices to communicate through UART from my ATTiny 44 to the PIC16F688 in the SparkFun SerLCD v2.5. I was not successful in sending data through PA3 which is connected to a header on my board. Following a suggestion by Tarek Mahmoud at Fab Lab BCN, I decided to look into the Software Serial library. If successful. I should input and output through any pin.

I started researching the DHT11 by reading the AOSONG Product Manual:

The component runs at 3.5V – 5.5V.

The DHT11 uses a single-wire, bi-directional, simplified single-bus communication. There is a 1 second unstable period after powering the device on. During this unstable period the component is calibrating for the environment. I will have to add a delay to the code for the module. Following the unstable period, the data pin on the component is set to input state and awaits messages from the microcontroller. Once the microcontroller sends an 80 millisecond (I believe, the document says “microsecond”) low signal, the DHT11 sends a high signal for 80 milliseconds. The actual data is transmitted in 40 bits: High Humidity, Low Humidity, High Temperature, Low Temperature, and Parity. The high values represent a whole number as an integer. The low values represent decimal values as integers. The parity should be the sum of all values in order for the reading to be correct.

I can check the values in this Binary calculator:

|

Binary |

Decimal |

High Humidity 8 |

0011 0101 |

53 |

Low Humidity 8 |

0000 0000 |

0 |

High Temperature 8 |

0001 1000 |

24 |

Low Temperature 8 |

0000 0000 |

0 |

Parity |

0100 1101 |

77 |

The DHT11 outputs the results of the last reading. For best results, the product manual suggests requests for readings at intervals greater than 5 seconds.

At ElectronicWings there is example code for reading the DHT11 with an ATmega16 or ATmega32. I will attempt to modify the code. This can be done two ways. First, I will output the data to the Arduino serial monitor through my FTDIBasic. Secondly, I will attempt to connect the input device board to the output device board. The second task may be something I want to handle during the network assignment.

The ElectronicWings example code is here:

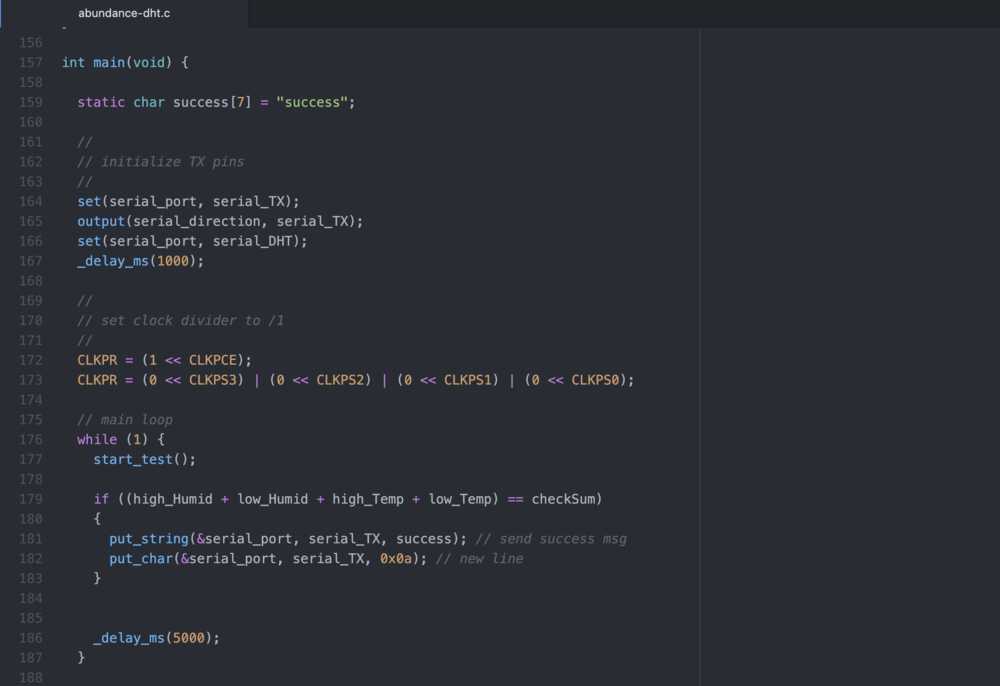

After several reviews of the documentation, I was able to alter the Arduino sketch and merge some of it with the Electronic Wings example. The ATTiny 44 will send a Request. The DHT11 will Respond. Each integer will be read into global variables that I can use to display the tempetrature and humdity. I fifth integer will be used as a checksum to verify the results. If the checksum fails, the microcontroller will output an error. This is preferred to displaying junk data.

- Design files: Right click + Save As

I started to recode the Arduino sketch for use with the AVR toolchain. I defined response, request, and read data functions. I based my code on the ElectronicWings example, my previous work in the Arduino IDE, and Neil’s examples for input and output devices.

The challenge to the coding was that the pin for the DHT11 had to constantly switch roles as an input and an output. Furthermore, I had to constantly refer back to my design in KiCAD to remind myself of my own board’s pin out. There was one point in which I connected the signal pin of the DHT11 module to a header that was not connected instead of PA3. I referred back to my LCD code from output devices and set a success and error message in the main function. I still need to be clear on how to concatenate string data. I thought displaying a success message, after doing a parity check, every five second interval would be enough for a break in work.

- Design files: Right click + Save As

Hero Shot - 2018

Current iteration of TXRX interface.

Fabricating the Board

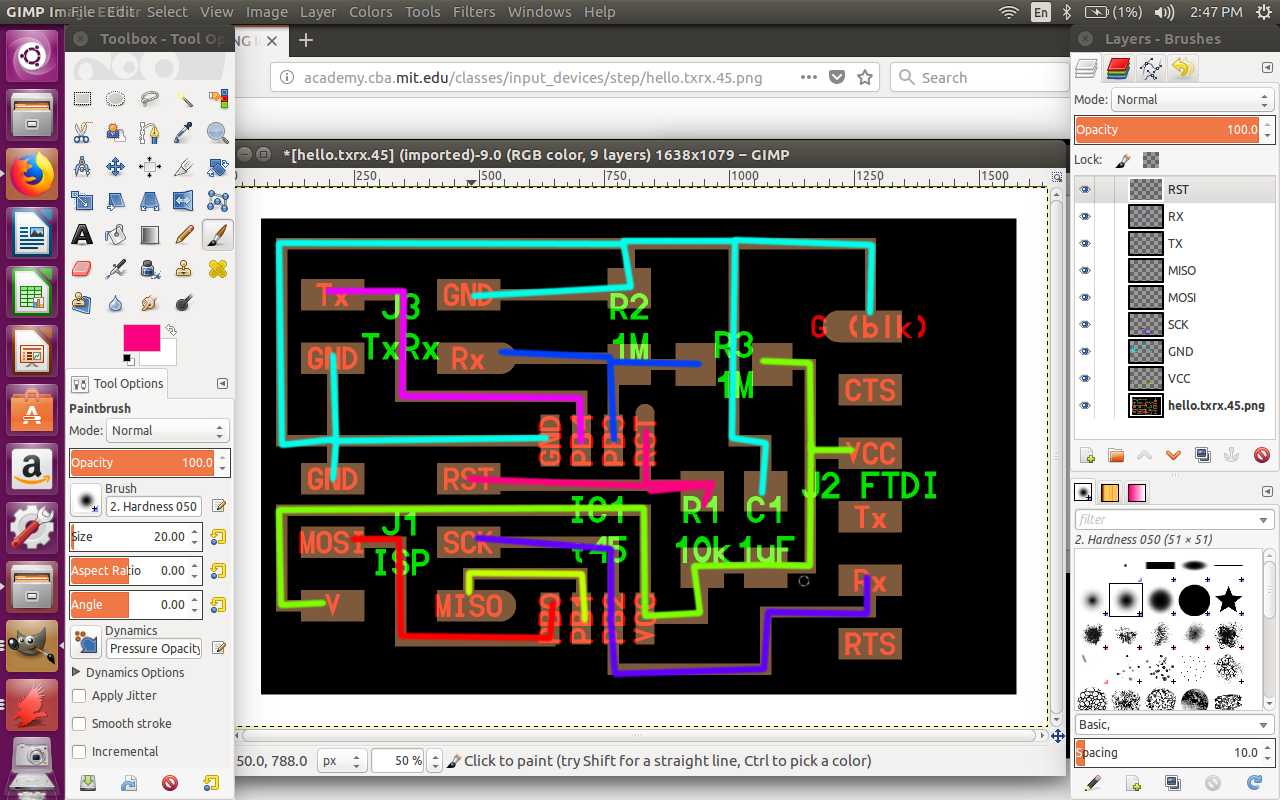

Copying the traces by connections via GIMP. Process detailed in Feb 28: electronics design.

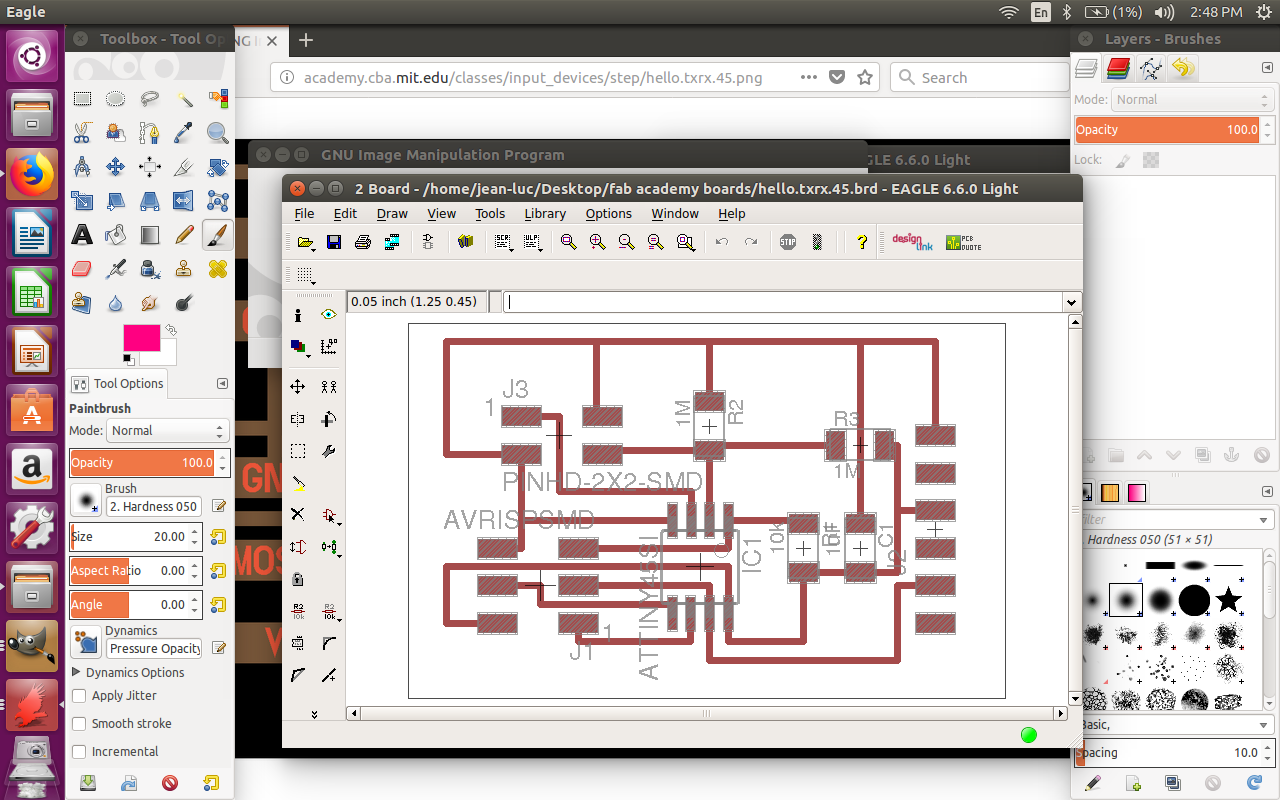

Routing the board in Eagle. Process detailed in Feb 28: electronics design.

Breaking down Neil's code

I started with the step response transmit-receive hello-world. This is set for a 9600 baud FTDI interface. The microcontroller is the ATTiny 45.

We start the main loop by setting the clock divider. This is covered in Embedded Programming. Afterwards, we initialize the output pins. serial_port is defined globally as PORTB. From the datasheet, Port B is defined as:

Port B is a 6-bit bi-directional I/O port with internal pull-up resistors (selected for each bit). The Port B output buffers have symmetrical drive characteristics with both high sink and source capability. As inputs, Port B pins that are externally pulled low will source current if the pull-up resistors are activated. The Port B pins are tri-stated when a reset condition becomes active, even if the clock is not running.

serial_pin_out writes logic one to PB2 which enabes the Analod to Digital Converter, Channel 1. serial_direction is DDRB which is define in the datasheet as the Port B Data Direction Register. DDR is an 8-bit register which stores configuration information for the pins, as stated here. Writing a 1 in the pin location in the DDR makes the physical pin of that port an output.

The transmit_port is also Port B, while transmit_pin is PB4. PB4 is the Analog to Digital Converter Channel 2. We first clear the transmit port and pin, before using the Port B Data Direction Register to set PB4 as an output.

//

// initialize output pins

//

set(serial_port, serial_pin_out);

output(serial_direction, serial_pin_out);

clear(transmit_port, transmit_pin);

output(transmit_direction, transmit_pin);

Next we deal with ADMUX, defined in the datasheet as:

The voltage reference for the ADC may be selected by writing to the REFS[2:0] bits in ADMUX. The VCC supply, the AREF pin or an internal 1.1V / 2.56V voltage referenc e may be selected as the ADC voltage reference. Optionally the internal 2.56V voltage reference may be decoupled by an external capacitor at the AREF pin to improve noise immunity.

The ADC module contains a prescaler, which generates an acceptable ADC clock frequency from any CPU frequency above 100 kHz. The prescaling is set by the ADPS bits in ADCSRA. The prescaler starts counting from the moment the ADC is switched on by setting the ADEN bit in ADCSRA. The prescaler keeps running for as long as the ADEN bit is set, and is continuously reset when ADEN is low.

//

// init A/D

//

ADMUX = (0 << REFS2) | (0 << REFS1) | (0 << REFS0) // Vcc ref

| (0 << ADLAR) // right adjust

| (0 << MUX3) | (0 << MUX2) | (1 << MUX1) | (1 << MUX0); // PB3

ADCSRA = (1 << ADEN) // enable

| (1 << ADPS2) | (1 << ADPS1) | (1 << ADPS0); // prescaler /128

At the beginning of the main loop we initialize two unsigned 16-bit integers up and down to 0. Each one describes when the transmit pin is set or cleared. Each time, we write logic one to ADSC to initiate a conversion. The values of up or down are added with the results from the Analog to Digital Converter to "save."

Later on, we send the binary values of the results either directly bitwise AND'd with 255 or right shifted 8 spaces.

This is all done in a for loop for nloop number of times which is defined globally as 100.

//

// main loop

//

while (1) {

//

// accumulate

//

up = 0;

down = 0;

for (count = 0; count < nloop; ++count) {

//

// settle, charge

//

settle_delay();

set(transmit_port, transmit_pin);

//

// initiate conversion

//

ADCSRA |= (1 << ADSC);

//

// wait for completion

//

while (ADCSRA & (1 << ADSC))

;

//

// save result

//

up += ADC;

//

// settle, discharge

//

settle_delay();

clear(transmit_port, transmit_pin);

//

// initiate conversion

//

ADCSRA |= (1 << ADSC);

//

// wait for completion

//

while (ADCSRA & (1 << ADSC))

;

//

// save result

//

down += ADC;

}

//

// send framing

//

put_char(&serial_port, serial_pin_out, 1);

char_delay();

put_char(&serial_port, serial_pin_out, 2);

char_delay();

put_char(&serial_port, serial_pin_out, 3);

char_delay();

put_char(&serial_port, serial_pin_out, 4);

//

// send result

//

put_char(&serial_port, serial_pin_out, (up & 255));

char_delay();

put_char(&serial_port, serial_pin_out, ((up >> 8) & 255));

char_delay();

put_char(&serial_port, serial_pin_out, (down & 255));

char_delay();

put_char(&serial_port, serial_pin_out, ((down >> 8) & 255));

char_delay();

}

}

At this point, I'm not too sure how to make changes to this code. I'll have to dig deeper in the archive to find an answer.

Design files: Right click + Save As

- Design files: Right click + Save As

Class Review 2016

João Leão, Fab Lab Barcelona, tried to do the step from Matt. The problems that he encountered were centered around libraries that needed to be installed. The attempt was around trying to run functions that were included in Node.js, which was a different version from his local installation. Neil reminded him to include design files for repo uploads. One comment that Neil made was that the black plastic connector on the FTDI connector should be mounted on the board. If this is not included in the design, every time the cable is connected to the board it will bend the solder joints.

Roman Kutyin, Fab Lab WOMA (Paris, France), proposed a project that would make an oximeter glow, which is a device that regulates breathing in life threatening situations. Neil asked if the blood oxygen would be measured by IR reflection? This was the proposed solution for Roman. There was a specific module discussed which Neil was concerned about in regards to price point. He then suggested to Roman to shop at a vendor like Digikey to be able to pick the frequency of emitters and detectors. In my personal experience, I select parts at Digikey but then take the manuafacturer part number and enter it into Octopart. The second site gives the availability of parts for a range of websites. Neil asked a follow up to Roman about the example of synchronous detection. Neil's solution is a scale down of a lock-in amplifier which is $1000s. The LED sends light out. The detector measures ambient light and the emitted light from the LED which is bounced off a finger. In the code, Neil measures the difference of the wave signal when the light is on versus when it is off. The smoothing filter is calculated by =(1 - E)filteredReading + EnewReading. Discussing his input devices project, Roman mentioned using assembly for the code. Neil advocated for the use of C, due to Roman's concern about speed. GCC-AVR, according to Neil, is a very good compiler and C has many single cycle hardware instructions that alleviate the concern of processing speed (with the caveat of dealing with data types that aren't primitive or multi-byte numbers). Aside from the concern about code, the design of the board was related to Roman's final project proposal.

Luca Giacolini, Fab Lab Toscana (Italy), did not have an input device for his final project. He designed a sensor breakout board which was based on previous board layouts in the repository. Neil liked the board as part of a breakout system, similar to an Arduino header. Luca not only milled PCB. He also used a Trotec fiber laser to etch into PCB, using a one micron fibre. Luca could not get the smoothest results, as he attempted to etch Daniele Ingrassia's satshakit. Neil said that this documentation was a good example of system architecture. Instead of making a monolithic system, Luca broke it apart and made modular components. In this way, Luca could incrementally debug subsystems. As a follow up, Neil reviewed capacitance. He covered two versions of capacitance. One was just loading. It measures whatever is in the vicinity out to the room ground, but that is a measurement of all loading. The other version includes a transmitter and a receiver. This is the preferred version as it allows the user to control, rather than relying on the room to help return. That second version creates a field which can sense when someone is pressing a button, but also when someone is going to press a button.

Diego Bustos, Fab Lab Yachay (Ecuador), started with the example on the class page. He encountered problems with the server connection to the Arduino and the PCB board. Previoulsy, he did make boards that work. What seemed to happen is that he was using the Arduino IDE to program the board, but Neil suggested that Diego use only the C code that was posted on the class page.

Dmitry Ershov, Fab Lab Polytech (Russia), etched onto a glass reinforced board. Neil reminded people of FR1 in the inventory. Milling of boards works with the FR1, but would break glass reinforced boards. Etching is fine, but creates a chemical waste that is an environmental concern. It also requires extra steps for the lithography.

Cindy Kohtala, Fab Lab Aalto (Finland), was not current; but she was working on a PhD dissertation and still managing to participate.

Bas Withagen asked a question about the DHT11 humidity sensor and the getting the component to work/fit with the ATTiny45. Fiore Basile said that the sensor does work. There are up to a dozen libraries to support. Neil advocated for capacitance as a way to DIY a humidity sensor.

Fiore Basile asked a question about the digital version of the MEMS microphone. This introduced the I2S protocol which seemed to be a "non-trivial" threshold for microcontrollers. Neil supposed that you may need to use an XMega board vs. an ATTiny. Working with the specific protocol would involve developing a codec. It is much simpler to use the analog version of MEMS and just do the A to D conversion. Bas added that I2S is a fairly old protocol which was used for 52 speed CD-ROM players.

Class Notes 2017

The goal is to take a microcontroller board that is an original design, add a sensor, and measure something. This can be used toward the final project.

We started by reviewing the ATTiny45 which is an eight pin AVR microcontroller. In the ATTiny45, there are multiple kinds of inputs. There are pins that read logic, high and low level. There's a comparator that reads the difference between two voltages. There's an A to D converter that measures absolute voltage. There's a counter that measures time and events. To understand the assignment, a comprehensive review is required.

Device communication is done through a serial interface. Installation on a host computer is required. PySerial through Node.js there are several options for a serial interface. Knowledge of bit timing is essential. Serial communication needs a 1% tolerance. To debug bit timing, the use of an oscilloscope is recommended.

Time delay can be set in the C code. In the clocks section of the microcontroller datasheet, there is detail regarding the OSCAL register. You can send values to that register to make time go faster or slower. The simpler solution is to set values in the C code. In the example of a switch, resistors pull up on the signal while a switch pulls the signal down.

For motion detection, there are pyroelectric sensors which measuring thermoradiation. A human body emits thermoradiation. Alternatively, Doppler radar is scaling down and can measure radio waves.

Sonar detection, requires a good reflective surface. Fuzzy or angled surfaces will cause a fault. Applications for distance measuring can be found in sinks and toilets. An alternative to sonar is time-of-flight detection which measures the reflection of light back from a reflective surface. Sonar can be good for measuring heights of liquids. Further reading into this subject, I found examples of trade off in regards to the Kinect sensor. Kinect I uses structured light. Kinect II uses time-of-flight which has a trade off between angled and dark surfaces. I thought of this because of recent articles about the applications of sensors and differing results with darker skinned people. The issue is with LED emission and whether or not a surface will reflect or absorb light which would cause a fault in detection.

Magnetic field detection, a hall sensor can detect the magnetic field of individual magnets or that of the Earth. Neil uses oversampling which measures the Anaog to Digital conversion many times. This oversampling improves the resolution of the results.

Neil showed an example of a browser-based interface graphing the results of a hall effect sensor. Browsers can not natively talk to serial devices. Certain browser do have extensions for serial communication. A solution that is cross-platform would be to code a webpage that opens a web socket that talks to a Jaavscript program. That program can use the Serialport library from Node.js to facilitate communication. The result is that the webpage talks to the server which communicates with the input device. The flexibility of this solution means that the webpage can be local or remote to the webserver.

Temperature detection is achieved through the use of thermistors. These come in two varieties, NTC and RTD. NTC can be more sensitive. RTD can be more accurate and operates at higher temperatures. The example board on the class page uses a "bridge" which is an important measurement concept. Further reading, I found a tutorial on this type of resistance bridge or "Wheat stone bridge". Measuring could happen with one fixed resistor and one variable resistor. What this does in the A to D is only slightly move the needle within the signal. This wastes to much of the A to D. Instead, we should measure "small change" within a "small signal". Using three fixed resistors and one variable resistor we can measure the differential within the ADC. In the code, Neil turns on the A to D and uses the hardware amplifier to amplify the difference. Digging further into the code, Neil uses a formula which approximates temperature. This is not sufficient for more precise thermometers. For that application, there are tables of the differences to temperatures. That said, the formula is a quick and dirty way to get started. The results are also filtered in the code, that is the resolution is increased by mixing new and old readings.

Light detection is achieved through the use of a phototransistor. Neil says a common misconception is that this is done through the use of a light sensitive resistor. Part of the issue of using a light dependent resistor is that some countries have banned them over the use of lead or cadmium which results in environmental safety concerns. In a circuit using a phototransistor, a pull up resistor goes to the A to D. The amount of light detected controls the current going through the transistor. Some phototransistors can see IR only. Some can see IR and visible light. Neil uses light detection to demonstrate synchronous detection. These present some of the same issues as time-of-flight due to the reflexion of skin color.

Accelerometer for detection of acceleration in X, Y, and Z axes. These sensors also measure gravity. The sensor uses I2C which will be discussed in Networking week. This protocol is a standard for device communications. Accelerometers are like processors with series of registers, each with a range of commands. A user needs to send commands to trigger readings and get results back. The one caveat to the accelerometer's popular use is that they universally come in tiny packages that are suited for smart phones. In order to use this device, you would have to use reflow to mount to the surface of PCB. The traces are a bit finer, but millable using the 1/64" end mill. In order to do reflow, you could use solder paste on the pads and heat the board in a frying pan or toaster oven. Another method involves tinning the pads, aiming a hot air gun, melting the solder which is supposed to suck in the piece. Reflow is required for the use of smaller parts. Accelerometers are further integrated with gyros that measure rotation, for about the same price.

Microphones with built-in amplifiers are also available. These, like the accelerometers, come in tiny packages that require the reflow method to mount to PCB surfaces. Microphones measure waves of sound as voltages. In the example code, Neil uses an array to capture a buffer of data which is then sent to the processor. The sound captured is not high fidelity, but it is voice quality. Previously, the fab lab inventory included hall effect sensors which were amplifiers and included in PCB designs. MEMS microphones are nicely integrated and make the use of hall effect amplifiers not necessary (for these designs). Analog microphones put out voltages only. Digital microphones are a bit more complex, as discussed in the 2016 class review.

Step response sensors can detect (almost) anything. Boards for these sensors are trivial in design. The complexity is on the software side with tricks for sampling data. Step response sensors function similarly to synchronous detection using phototransistors. Instead of an emitter and detector sampling visible or IR light, step response sensors use electrodes that emit and detect charges and interruption in circuit flow. A pulse of charge is sent through the circuit. This is filtered to smooth background noise. Differences in the highs and lows of the signal are calculated to measure changes within the electric field. In this way, we can make buttons that can be pressed or know when they are about to be pressed. A single electrode input goes out to room ground, which makes it unreliable in various environments. Two electrodes use the synchronous detection method and work when a circuit is completed between the emitter and detector. Many things can be measured with step response sensors, and can be achieved with a simple PCB design with electrodes cut on the vinyl cutter.

There are several other types of input devices that Neil did not spend too much time covering. Transducer piezos can measure vibration and time-of-flight. Force sensors are a bit nasty. As an alternative to these, Neil suggests capacitance sensors to measure force. Image is detected by the use of cameras. These have scaled down. Webcams are only a few dollars. Single board Linux computers can connect to these through USB and Javascript.

Sources

Pöhlmann, Stefanie T. L. et al. “Evaluation of Kinect 3D Sensor for Healthcare Imaging.” Journal of Medical and Biological Engineering 36.6 (2016): 857–870. PMC. Web. 10 Oct. 2017.

Smith, Adam. “These automatic soap dispensers don't work for black people.” Metro, 13 July 2017, metro.co.uk/2017/07/13/racist-soap-dispensers-dont-work-for-black-people-6775909/.

“Photo Resistor.” Light Dependent Resistor (LDR) » Resistor Guide, www.resistorguide.com/photoresistor/.

“Wheatstone Bridge Circuit and Theory of Operation.” Wheatstone Bridge Circuit and Theory of Operation, www.electronics-tutorials.ws/blog/wheatstone-bridge.html.