Computer-controlled cutting.

// weekly schedule

| Time block | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun | Mon | Tue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global class | 3 h | ||||||

| Local class | 2 h | 4 h | |||||

| Research | |||||||

| Design | 1 h | ||||||

| Fabrication | 1 h | 3 h | |||||

| Documentation | |||||||

| Review |

//overview

This week we get hands-on with two machines: the laser cutter and the vinyl cutter. The big task is designing a parametric press-fit construction kit — pieces that hold together without glue, just by friction. We also need to cut something on the vinyl cutter and, as a group, characterize the laser cutter in our lab.

//assignments

- Group assignment: Lab safety training done. Laser cutter characterized.

- Individual: Parametric press-fit kit designed and cut.

- Individual: Vinyl stickers cut.

- Design files included.

//group assignment

Safety training.

First things first — before touching any machine, I went through the safety training at Fab Lab León. The main rules for the laser cutter: never leave it running unattended, always check the ventilation is on, only use approved materials (absolutely no PVC or polycarbonate — they release toxic fumes), and keep the lid closed while cutting.

After the training I signed the safety form confirming I understood everything and was ready to use the machines.

Link to group page.

The group assignment for Fab Lab León 2026 is here:

Fab Lab León 2026 — Group assignments

Laser cutter characterization.

For the group assignment, we traveled from León to the Fab Lab in Ponferrada together with our local instructors. That’s where we did the hands-on characterization of the laser cutter, the press-fit comb test, and got familiar with the machine and its workflow.

The laser cutter we used is a Framun Laser NOVA ELITE 14, a CO2 machine with 130W of power and a pretty generous working area.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Model | Framun Laser NOVA ELITE 14 |

| Laser type | CO2 (glass tube) |

| Power | 130 W |

| Working area | 1400 × 900 mm |

| Max cutting thickness | 0–30 mm (depends on material) |

| Focus distance | 7 mm |

| Software | RDWorks |

Before every job we turned on the extraction and filtration system. The machine has air assist as well, which helps reduce flare-ups and keeps the cut cleaner. After finishing, we waited a few seconds before opening the lid to let the fumes evacuate.

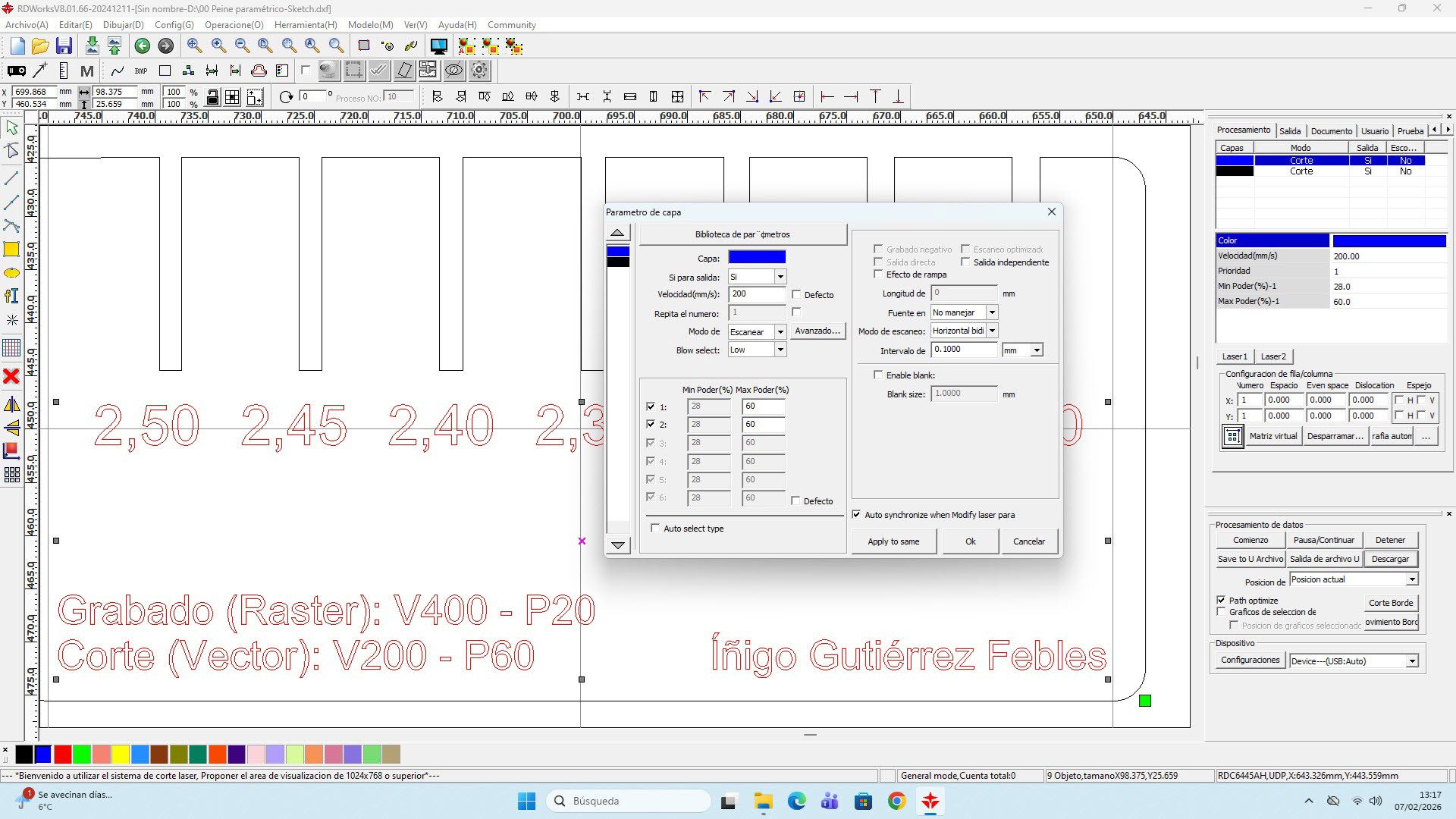

Software workflow.

This machine uses RDWorks instead of Rhinoceros. The workflow is a bit different from what I was used to seeing at León:

- Import or create the design in RDWorks.

- Assign layers by operation type — raster/scan for engraving, cut/vector for cutting. Important: always set engraving layers to process before cutting layers.

- Configure speed, power (min and max), and set Blow Select to LOW.

- Send the file to the machine via the Download button (file name max 8 characters).

- On the machine: set origin, adjust focus using the 7 mm gauge, run FRAME to verify the job fits inside the material.

- Turn on extraction, close the lid, press START, and supervise the entire process.

Cutting parameters for corrugated cardboard.

These are the parameters I used for 2.3 mm corrugated cardboard on the Framun:

| Operation | Speed | Power |

|---|---|---|

| Cut (vector) | 200 | 60 |

| Engrave (raster) | 400 | 20 |

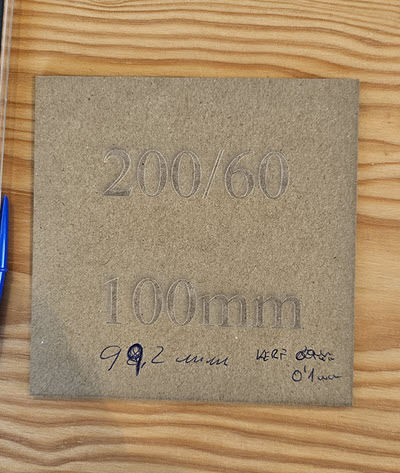

Kerf.

To calculate the kerf, we designed a 100 × 100 mm square, cut it, and measured the result with a digital caliper. The measured piece came out at 99.8 mm instead of 100 mm.

Since the laser removes material on both sides of the cut line:

Kerf = (100 − 99.8) / 2 = 0.1 mm per side

This value can change depending on material type, thickness, focus accuracy and cutting parameters, so it’s always a good idea to re-test when switching materials.

What I learned from the group work.

Going to Ponferrada was useful because I got to see a different machine and a different software workflow (RDWorks vs Rhinoceros + Epilog driver). The fundamentals are the same — layers, parameters, test cuts — but the interface and some details change. It also reinforced the idea that parameters are never universal: even with the same material, each machine has its own sweet spot. Always test before committing.

//individual assignment — Laser cutting.

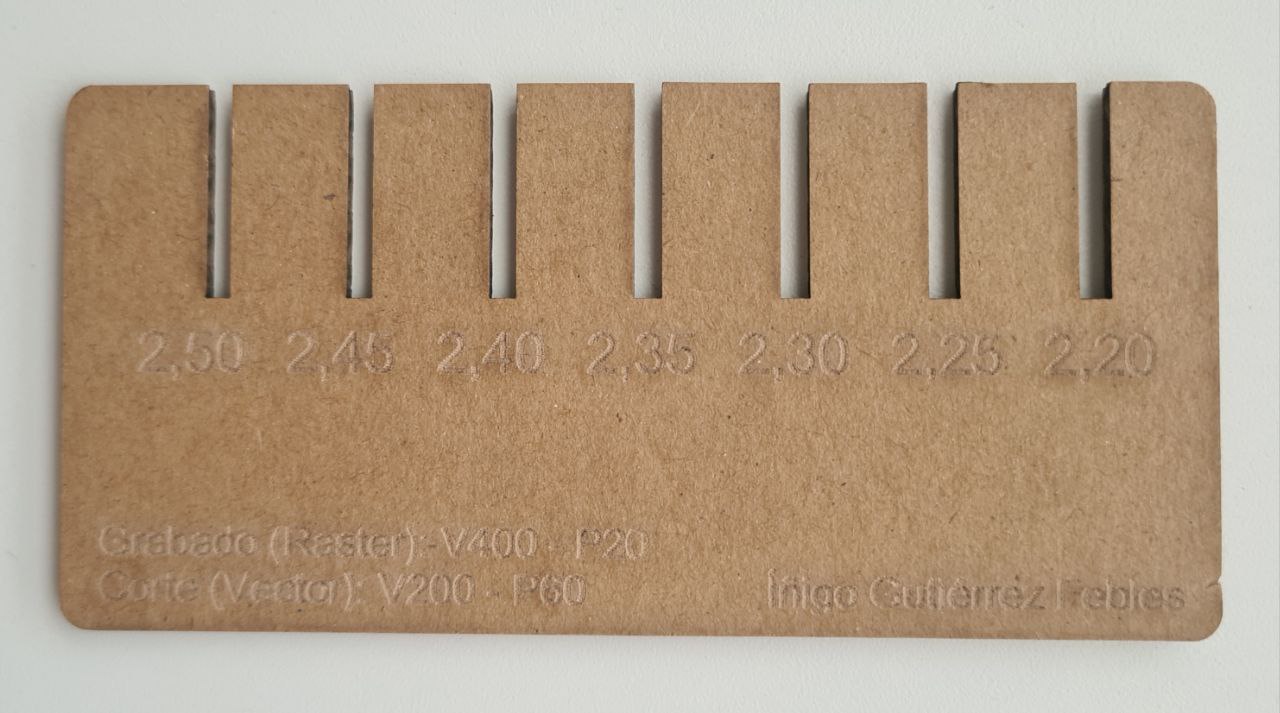

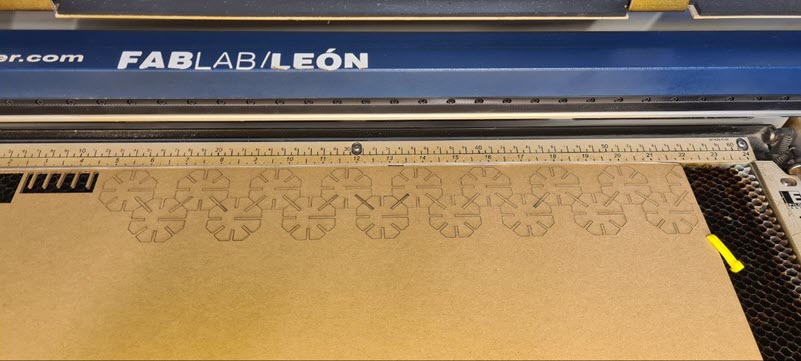

Press-fit test (the comb).

Before jumping into the final design, I needed to figure out the right slot width for a good press-fit in my material. I used a pre-designed measurement comb — basically a piece with several slots of slightly different widths, each one labeled. The idea is simple: cut it, try fitting pieces into each slot, and see which one grabs best.

The comb had slots ranging from about 2.0 mm to 2.6 mm in 0.1 mm steps. After testing, the sweet spot was 2.20 mm — tight enough to hold, loose enough to assemble without forcing.

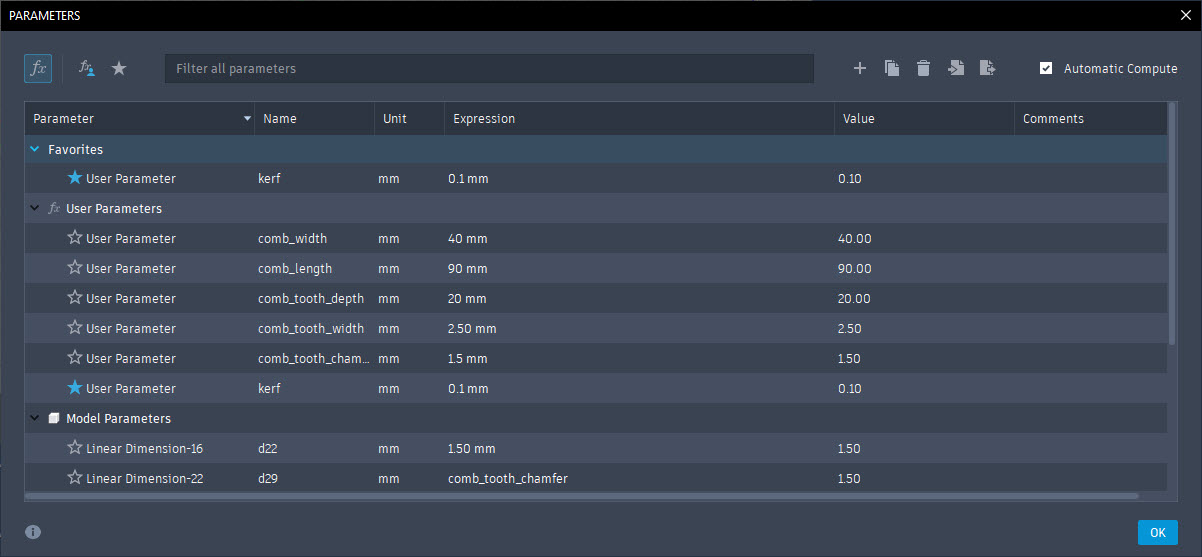

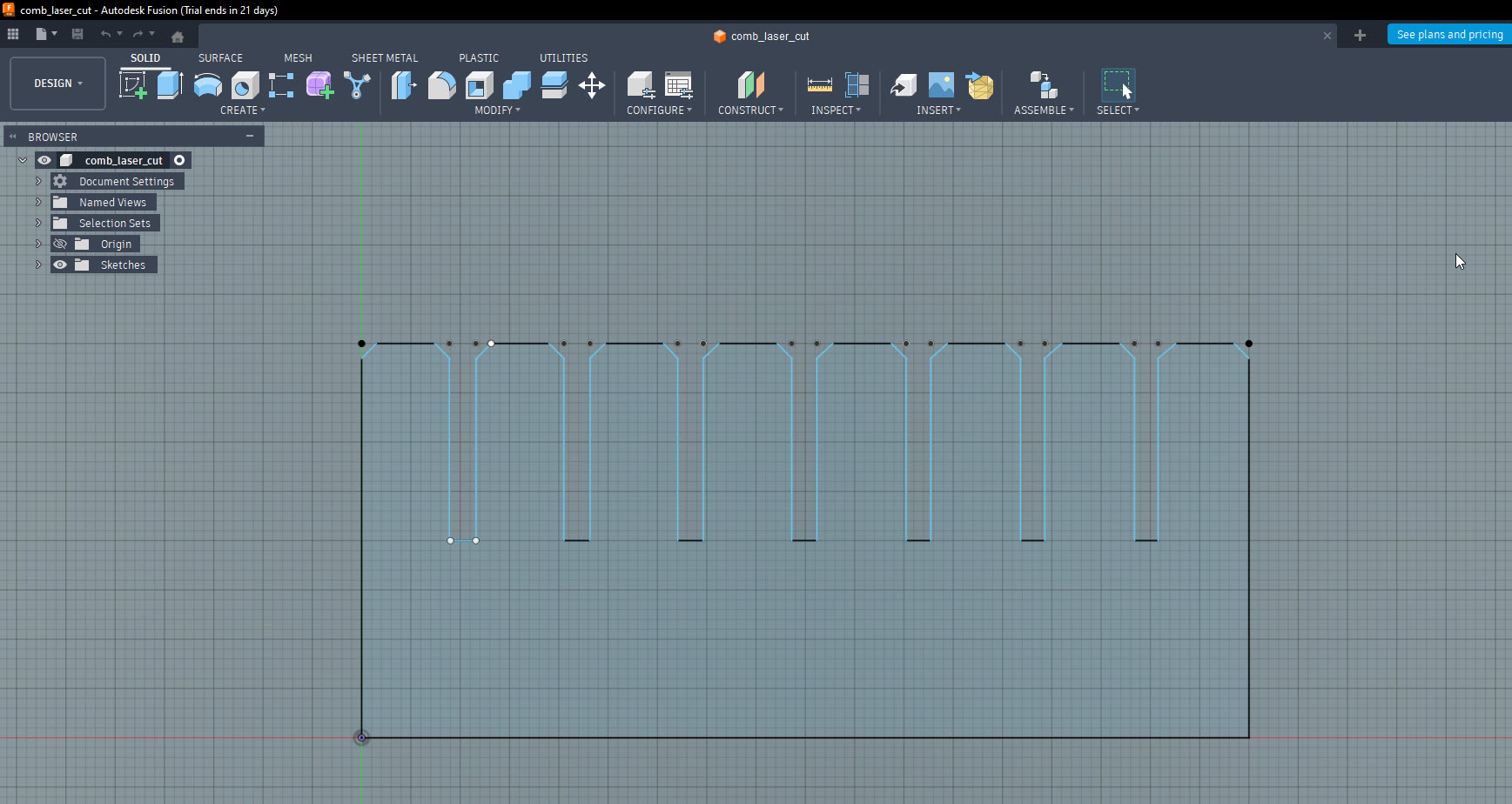

Parametric design in Fusion 360.

I used Fusion 360 for the parametric design. The key idea behind parametric design is that you define dimensions as variables instead of fixed numbers. So if I change the material thickness from 2.3 to 3.0 mm, every slot in the design updates automatically. Very handy.

User parameters.

In Fusion I went to Modify → Change Parameters and created these variables:

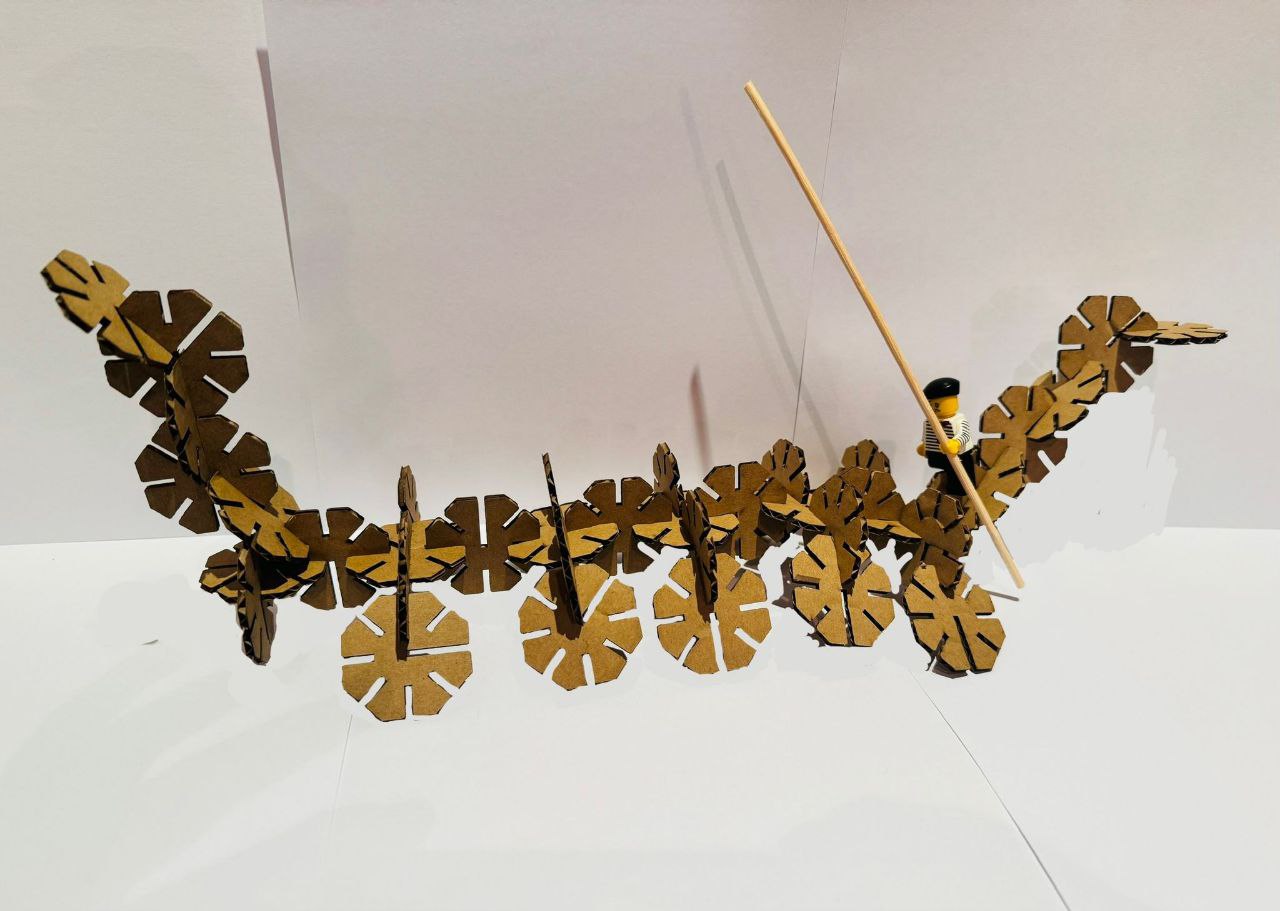

Design concept.

I got the inspiration from Joanne Leong’s work in the MIT “How to Make (almost) Anything” course (Fall 2021). She used an octagon-based piece with slots at 90° and 45° to build a dragon — I loved the idea of starting from a simple polygon and getting organic shapes out of it.

The piece has seven identical slots around the perimeter and one deeper slot that serves as a differentiated connection point. This asymmetry lets you connect pieces in different orientations and build varied structures from a single piece type.

The whole point was: one piece, many copies, lots of possible shapes when you start assembling. In my case, I went for a gondola instead of a dragon.

{/* screenshot of the Fusion sketch */}

From FreeCAD to the laser, and now to Fusion 360.

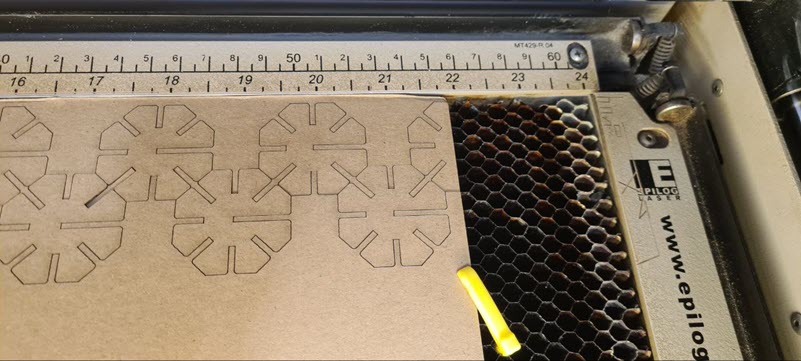

For the actual laser cutting, I used Joanne’s original FreeCAD file, adapting the slot width parameter to match my material (2.3 mm cardboard, 0.1 mm kerf). I exported the DXF from FreeCAD, imported it into Rhinoceros, and cut the pieces on the Epilog Mini 24 at Fab Lab León.

One thing to watch out for when exporting DXF from FreeCAD: always double-check dimensions in Rhino before sending anything to the laser, as scaling issues can happen.

Fusion 360 — Work in progress: I’m currently working on recreating the same parametric design in Fusion 360, building it from scratch to better understand the parametric workflow and to have full control over the user parameters. This will be updated soon.

Export to DXF.

Once the design was done, I exported it as a .DXF to open it in Rhinoceros. One thing to watch out for: Fusion sometimes changes the scale when exporting to DXF, so I always double-checked dimensions in Rhino before sending anything to the laser.

Cutting the pieces.

In Rhinoceros, I arranged multiple copies of the piece on the cardboard area to get as many as possible with minimal waste. Then I followed the standard workflow: layers with the right colors, fine line widths, parameters from the characterization tests, origin set on the machine, ventilation on, and eyes on the machine the whole time.

The Gondola.

With all the pieces cut, I assembled them into a gondola. This was a fun way to show that the kit can produce complex 3D shapes from a single piece type.

The press-fit joints hold firmly — you can pick up the whole structure and it stays together, no glue needed. The corrugated cardboard helps here: the internal wavy layer acts like a small spring inside the slot, which adds grip.

And because why not, I made a quick photomontage placing the gondola in Venice, floating next to the Rialto Bridge.

//individual assignment — Vinyl cutting.

The machine.

For vinyl cutting I used the Roland GX-24 at the lab. It’s a pretty straightforward machine — a small blade moves over the vinyl sheet and cuts along vector paths.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Model | Roland CAMM-1 GX-24 |

| Max cutting width | 584 mm |

| Max cutting speed | 500 mm/s |

| Blade angle | 45° |

| Software | Rhinoceros + Roland CutStudio driver |

{/* PLACEHOLDER: photo of the Roland GX-24 */}

Design.

I wanted to make custom stickers for my notebook with my professional brand name: “rocinant //”. I made two versions — one in white vinyl and one in green vinyl — to see which one worked better on the dark cover.

The design was done as vector paths. Important: text needs to be converted to outlines before cutting, then transform into a path, otherwise the machine won’t know what to do with it.

{/* PLACEHOLDER: screenshot of the design file */}

Cutting process.

The workflow:

- Loaded the vinyl roll into the Roland, aligned it with the rollers.

- Selected “Roll” mode on the machine.

- Sent the design from Rhino through the Roland driver.

- Used “Get from machine” to check available material size.

- Set cutting parameters: speed PLACEHOLDER cm/s, force PLACEHOLDER gf.

- Ran a quick test cut — small circles and a cross. If they peel off cleanly without cutting the backing, the pressure is right.

- Cut the final design.

{/* PLACEHOLDER: fill in speed and force values */}

Weeding and application.

After cutting, I removed the excess vinyl around the letters (this is called weeding). Then I applied transfer tape over the design, pressed it down, peeled the backing, and stuck it on the notebook. Straightforward process, but you need patience with small details — the letters can lift if you rush it.

Result.

Both came out clean. The white version is more readable, but the green one looks better on the dark cover — more subtle and matching my brand color. I’m keeping the green one for daily use.

//Reflection.

This was my first real week working with fabrication machines, and the biggest lesson was how iterative the whole process is. You don’t just design and cut — you characterize, test, measure, adjust and test again. The parametric approach saved me a lot of time because once the variables were set up, adapting the design was just changing a number.

Building the gondola was probably the most satisfying part. It’s one thing to design a single piece on screen, but seeing dozens of them come together into a 3D structure that actually holds — that felt like proper digital fabrication. Also, having the chance to meet in person my fellow colleagues in Ponferrada, as well as, Javi, the local instructor there, was amaizing.