Project Development

Week 1:

This week, I was able to dive deeper into my project by focusing on many of the "how" questions. I worked on different aspects of my final project, including the basic reference circuit, the key components needed, and a sketch of the final design. It wasn't much, but I am happy with the progress made this week and I was able to learn a lot this week from all those activities.

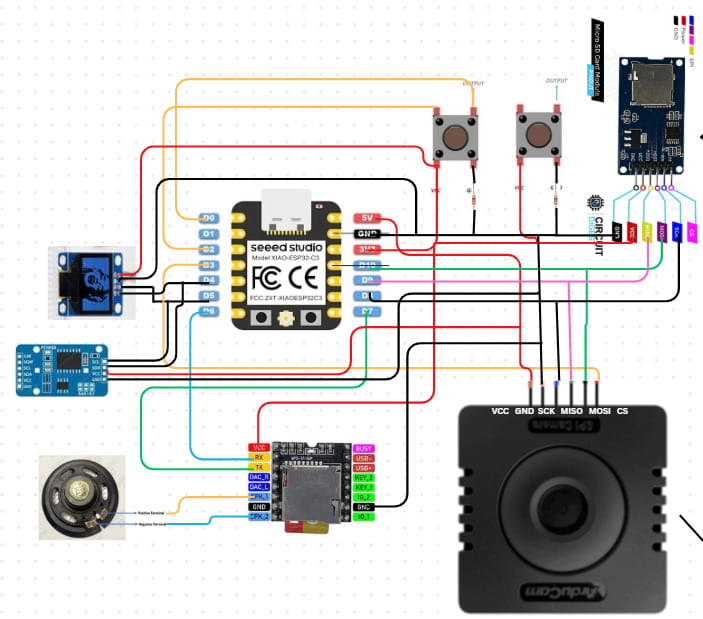

Reference Circuit:

We made a basic circuit for practice in Canva using the key components we listed. I was a complete beginner when it came to circuits and how the connections worked so I had a hard time understanding everything but my instructor helped a lot with everything. This is the reference circuit we made in canva:

These are some of the things I learned that time:

- Choose the components: First, identify the specific components you need for your circuit.

- Check compatibility: Make sure each component can work with your board. A good way to do this is by searching the component name along with the board (e.g., “DS3231 RTC Arduino”) to see if it has been done before. This helps avoid last-minute issues with incompatible parts. Save the connection reference that is the clearest to you.

- Find the pinouts: Look up the pinout for each component (for example, “Arduino pinout” and “DS3231 RTC pinout”). The pinout tells us the specific connection for each pin. Each pin has a specific function, so it’s important to check the pinout of both components when connecting them. Some pins are meant to receive input from a specific output pin, while others send output. Each pin handles a particular type of signal, like power, ground, or data, and connecting the wrong pins can cause the circuit to fail or even damage components. There are many references, like images, showing the pinouts of components. Save the one that is the clearest and most detailed for your use.

- Connect the pins: Using the connection reference and the pinout information, connect the required pins carefully, making sure each pin goes to the correct spot.

- One more thing to keep in mind: all the GND (ground) pins in a circuit should be connected together. This creates a common reference point and provides a path for electricity to safely flow back to the source, completing the circuit.

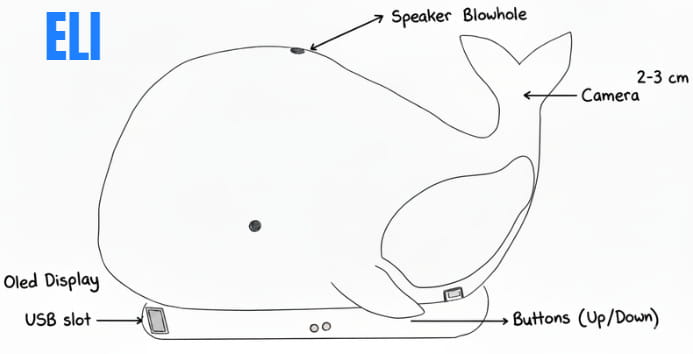

I was also able to make a draft sketch for my final project. Although it isn't very detailed, it represents what I have in mind for now, even though it will likely change a lot as the project develops. I then refined the image using Gemini AI, so credit goes to Gemini AI.

That's all for this week.

Week 2:

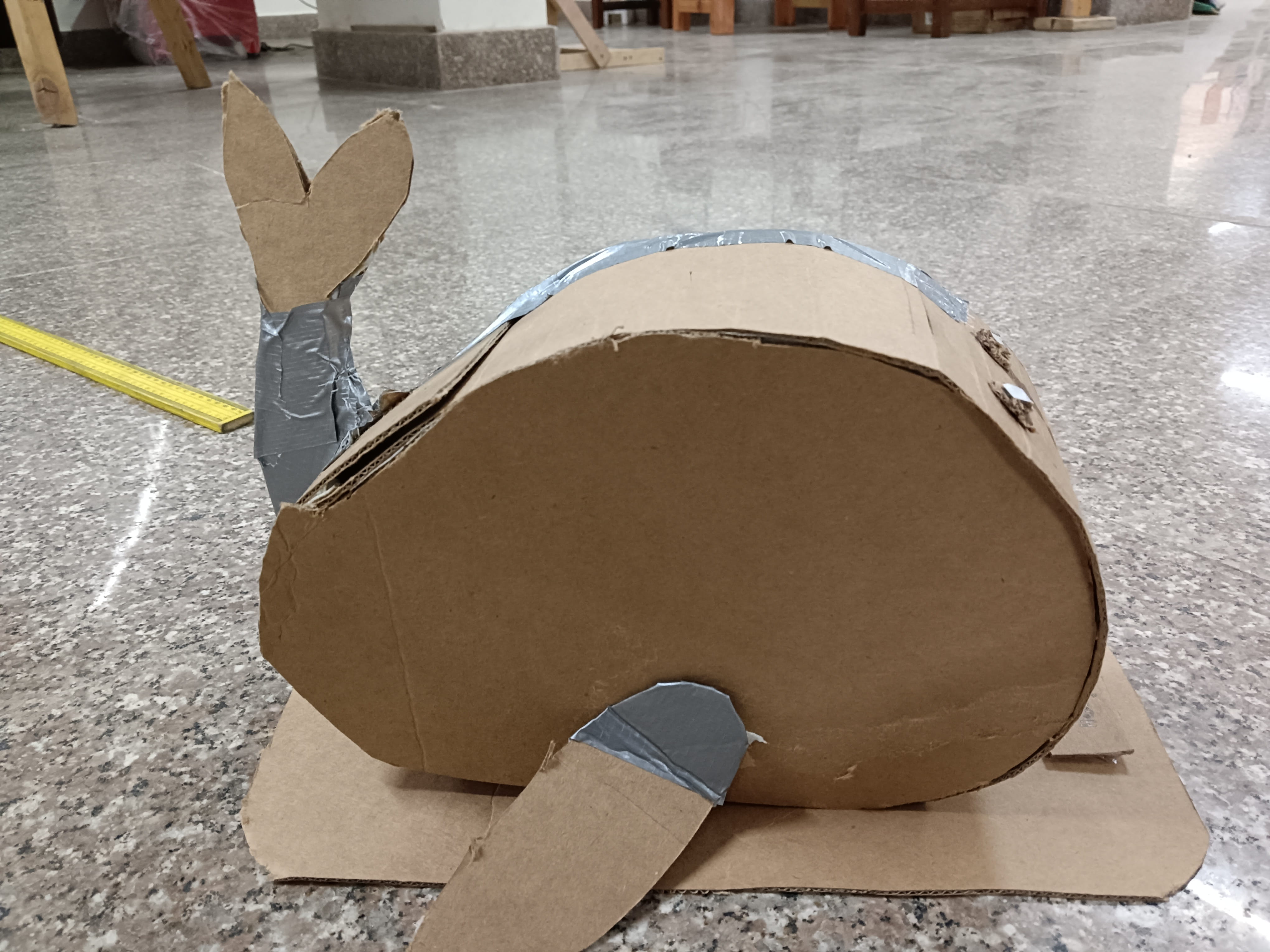

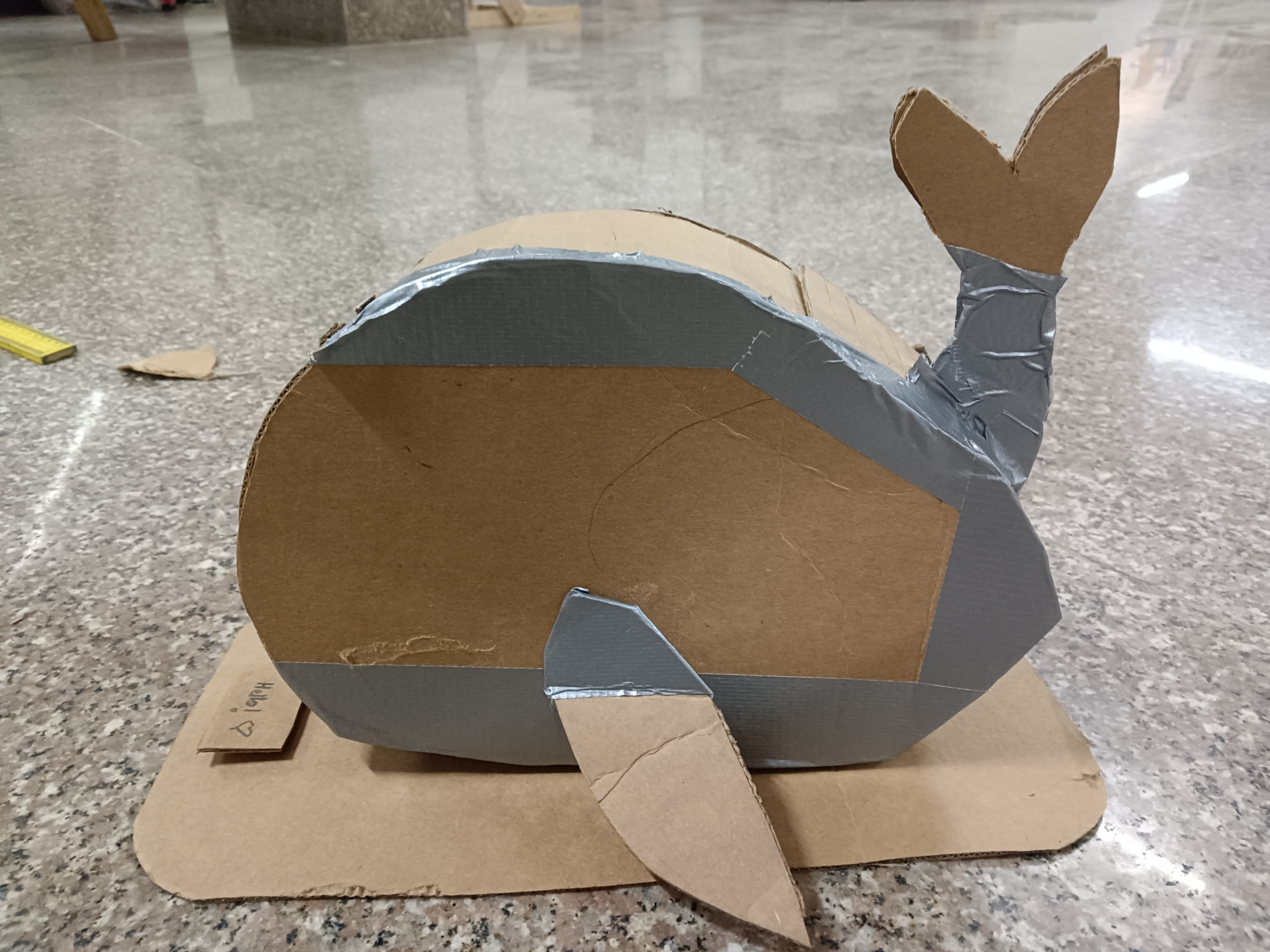

This week, we went to the lab to do cardboard prototyping. We created detailed cardboard versions of our final projects to better understand how all the components would work together, visualize the final design, and identify gaps that needed improvement.

This was my prototype of my final project which is a desk bot that trains your focus. For more details about my project, you can visit the Project Proposal page on my website.

Through this experience, I was able to identify several gaps in my project idea and realized that I needed to work out many details instead of keeping everything abstract in my head.

Gaps such as:

- Camera orientation: Where will the camera/cameras be placed? On the tail or on the front of the body?

- Input method: How should users input data? (Fins, buttons, sensors, etc.)

- Casing: How can I open the bot easily to check internal components?

- Data Logging: How can data be logged efficiently without making the process too complicated?

- Menu Structure: What should the home menu look like and how should navigation work?

- Measurements: What are the exact measurements for internal and external fits?

- Internal Layout: How should connections be arranged for correct component placement?

Reviewing these gaps, I can categorize them into three core challenges for Phase 2:

1. User Interaction & Interface (UI): Input method and menu structure.

2. Mechanical Design: Camera placement, casing, and internal layout.

3. Data and System Architecture: Core logic and efficient logging.

For next week, I will try to focus on resolving the UI and mechanical design gaps as much as I can at first, since those decisions will directly affect data logging and internal connections.

Note to self: Make a detailed sketch of the final project from all views (top, side, back, front) and label as many components as possible once the camera placement and input button decisions are finalized.

Week 3 – User Interface & Menu Structure Design

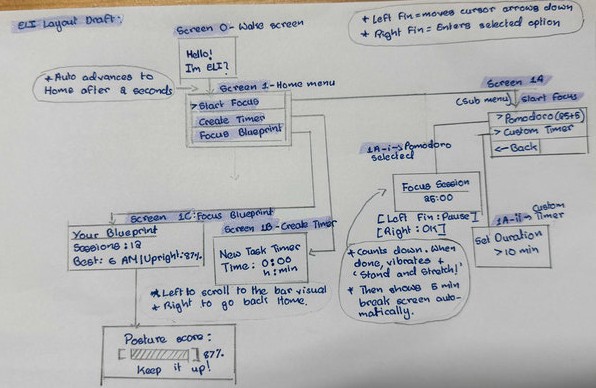

This week focused on developing the menu architecture and overall interface layout. My initial approach was intentionally minimal, without defining detailed interaction logic. However, I recognized that neglecting interface design could weaken the usability of the final project.

To improve the design, I shifted my perspective from creator to end user, prioritizing clarity, simplicity, and intuitive navigation.

Initial Concept (First Draft)

Hello!

→ Start Focus Timer

→ Show Blueprint

→ Set Custom Timer

While functional as a concept, this structure lacked essential interaction details, particularly:

- How users would configure timers

- How input values would be entered

- How navigation between options would occur

To improve the structure, I asked Claude AI for feedback on the menu organization. Based on the suggestions, I redesigned the interface by dividing features into different screens and organizing them more clearly. This was the prompt I used and I even pasted my project proposal and initial documentation on the project to help the AI get a clearer understanding on my project.

Revised Menu Structure (Draft)

Screen 1 – Home

A → Start Focus

B → Create Timer

C → Focus Blueprint

Screen 1-A – Start Focus

I → Pomodoro Mode

II → Custom Timer

I made a draft on paper to help me get a clearer idea:

I made a flowchart to make it easier to understand as well.

E.L.I. Whale Bot Flow

Interface Logic & Navigation

Create Timer

Focus Blueprint

Custom Timer

Global Navigation Rules

Considerations for Week 4

-Input Method Exploration

I am currently exploring flex sensors as the main input method.

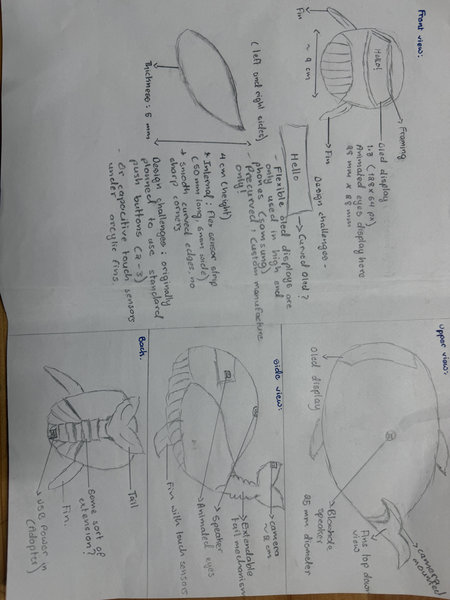

This is a rough sketch I created of my bot from different views. I tried to include as many details as possible, but at this stage, this is the level of detail I was able to develop. The sketch helped me visualize the overall form and layout of the design. However, I still need to work further on the interior build and internal component placement.

Questions I'm still figuring out:

- How well can flex sensors handle menu navigation?

- Can different bend angles act as different commands?

- Using only two fins for navigation may be limiting. One possible solution:

Single press / bend → Scroll

Double press / bend → Select

Long press / sustained bend → Return Home

If flex sensors are confirmed for the final project, I will need to:

- Define gesture thresholds

- Calibrate sensor readings

- Build a reliable interaction model

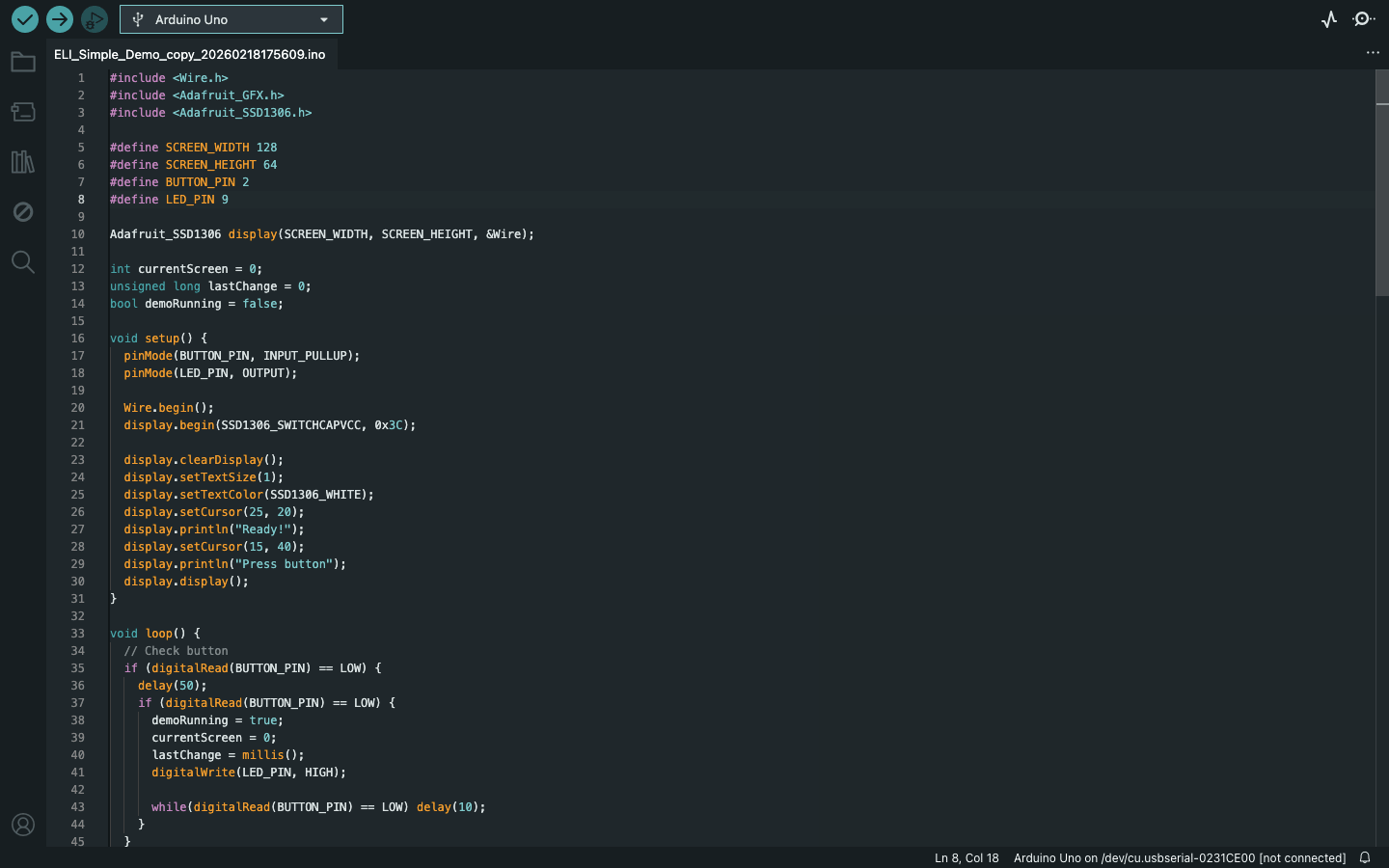

Week 4: Making a simple simulation to demonstrate the menu structure.

For this week's project development, since we learned about embedded systems, I wanted to work on my final project simultaneously as well. Instead of starting something completely new, I decided to make a simple demonstration of the menu structure I had designed earlier.

I began by creating a basic simulation in Wokwi, using the draft menu layout I made last week.

In Wokwi, I added the components needed for the simulation: an ESP32-C3 microcontroller, LEDs, resistors, a breadboard, and an OLED display. The simulation itself is very simple, it just cycles through the different menu screens to give a rough idea of how the interface might look. At this stage, the goal was mainly to visualize the flow rather than build a fully interactive system. I plan to improve this later by adding proper inputs and navigation logic.

This is the first simulation I made, which only had a few components:

This is the second video, which has more components, and I updated the code to cycle through different menu structure for the demonstration:

You can access my Wokwi simulation here.

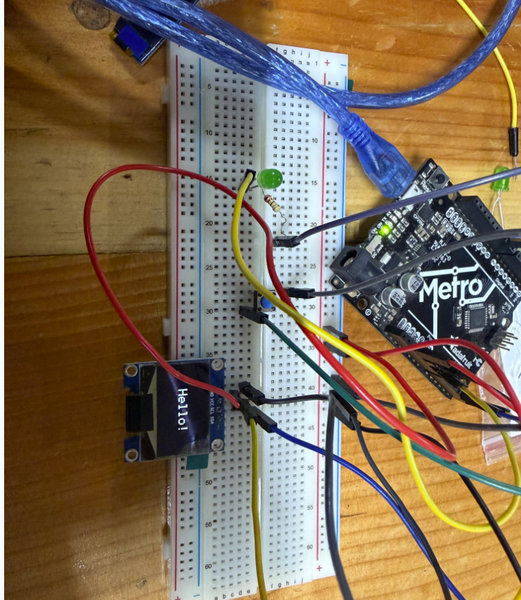

After testing the simulation, I tried building the same circuit using real hardware. I first used a Seeed Studio XIAO ESP32-C3 (bare module), since there wasn't enough time to design and fabricate a custom board. I placed it on a breadboard and wired the connections similar to the simulation. However, the setup didn't work as expected. To keep the demonstration moving, I switched to an Arduino Metro board instead. The hardest part was to program the OLED display, instead of working like the simulation, it got stuck at 'Hello'. After a lot of time spent on trying to get the OLED to cycle through different screens, it turns out the code was too long for the OLED to work so I used Claude AI to shorten the code. And it finally worked.

Here is the video:

This week, since I had to browse through a datasheet for a microcontroller, I browsed through the datasheet for the microcontroller I'll be using for my final project as well, which is the Xiao ESP32 C3 microcontroller.

.jpg)

(1).png)

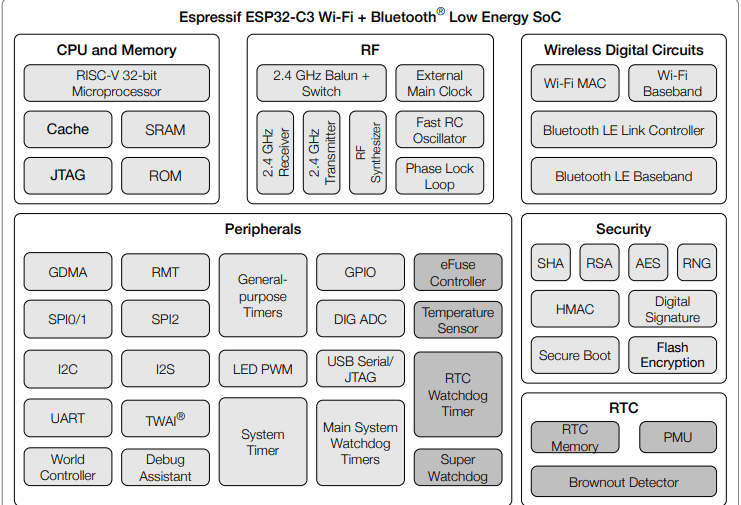

The image below shows the ESP32 microcontroller's functional block diagram:

The chip is divided into 6 main sections:

- The brain of the chip. The processor is a 32 bit RISC-V core, which is a modern, energy efficient type of processor. When you upload code from Arduino IDE or similar, it ends up here. The SRAM is like short term memory (used while the program runs), the ROM has built in bootloader code from Espressif that you can't change, and the Cache speeds things up by keeping frequently used data close to the processor. JTAG is a debugging interface used during development.

- RF (Radio Frequency): This handles all wireless communication. It has a 2.4 GHz receiver and transmitter, a balun/switch to toggle between Wi-Fi and Bluetooth, and clock/oscillator circuits to keep timing precise. You don't interact with this directly — the firmware handles it.

- Wireless Digital Circuits: This is the software-side of wireless — the Wi-Fi MAC, Wi-Fi Baseband, and Bluetooth LE controller and baseband. These work with the RF section to give you actual Wi-Fi and BLE functionality out of the box.

- Peripherals: The most relevant section for your project. This is everything you can physically connect to:

- SPI, I2C, I2S, UART: standard communication protocols for sensors, displays, etc.

- GPIO: general input/output pins

- ADC: reads analog signals (sensors, potentiometers)

- LED PWM: controls LEDs or motors with PWM signals

- USB Serial/JTAG: used for programming and serial monitor

- Timers & Watchdogs: keep your program running reliably and handle crashes

- GDMA, RMT, TWAI:

- GDMA (General Direct Memory Access): normally the CPU handles every data transfer happening inside the chip, which takes up processing time. GDMA takes that job away from the CPU and handles it independently in the background, freeing the processor to focus on running your actual program.

- RMT (Remote Control Transceiver): was originally designed for infrared signals like a TV remote. It generates very precisely timed pulses, which is hard to do reliably in regular code. Because of this, it's now commonly used to control addressable RGB LEDs like NeoPixels, which require exact timing to set colors correctly.

- TWAI (Two-Wire Automotive Interface): is a communication protocol originally developed for cars, allowing different modules to talk to each other reliably over just two wires. It's built to work in electrically noisy environments, making it suited for automotive or industrial projects.

- The ESP32-C3 has dedicated security circuits built directly into the chip as actual hardware rather than software, making them faster and harder to bypass. These circuits handle data encryption, generate secure random numbers for encryption keys, verify that data and firmware haven't been tampered with, ensure only trusted code runs on the chip, and protect stored code from being physically read off the chip.

- RTC (Real-Time Clock): Has its own memory (RTC Memory) and a PMU (power management unit) for deep sleep modes, plus a Brownout Detector that resets the chip if power drops too low, useful for battery projects.

Week 5: Testing flex sensors for my user interface.

This week, I built upon my existing circuit to test the menu navigation using a flex sensor instead of physical buttons since I will be using flex sensors as my main input method. The interface now responds to different levels of bend:

- A light press scrolls through the menu options.

- A longer, deeper press confirms a selection.

I also implemented both visual and audio feedback: the LED blinks and the buzzer beeps to confirm each scroll and selection. Although the timer functions aren't fully programmed yet, the menu structure responds reliably to the flex sensor, which was the main goal for now.

You can download my Arduino code here.

Week 6: Designing the PCB for my final project using KiCad

This week, after learning how to create schematics and design a PCB, I tried making a PCB for my final project. The board includes a Xiao ESP32-C3 module and connector pin headers for my components. It took a long time to get everything right since I’m still a beginner, but the PCB design turned out well. Although it will likely need many modifications as my final project idea becomes clearer, this design serves as the first draft and the foundation for all future PCB designs for my project.

This is the schematics:

.jpg)

And this was the pcb I deisgned for my final project :

.jpg)

I also generated an RML file for the PCB design, so it’s ready to be milled next time.

.jpg)

.jpg)

I got to think about the components in detail for my final project too:

You can access the component list here.