Week 4: Embedded Programming

This week is focused on understanding and working with embedded systems in practice. For the group assignment, we’ll demonstrate and compare different toolchains and development workflows used for various embedded architectures, so we can understand how programming and debugging differ across platforms. For the individual assignment, I’ll dive into a microcontroller datasheet to understand its features and architecture, then write and test a program on a microcontroller-based system that interacts with input and/or output devices and communicates through a wired or wireless connection. Essentially, this week moves from theory into actually reading, programming, and making a microcontroller do something real.

Saheen guided us this week.

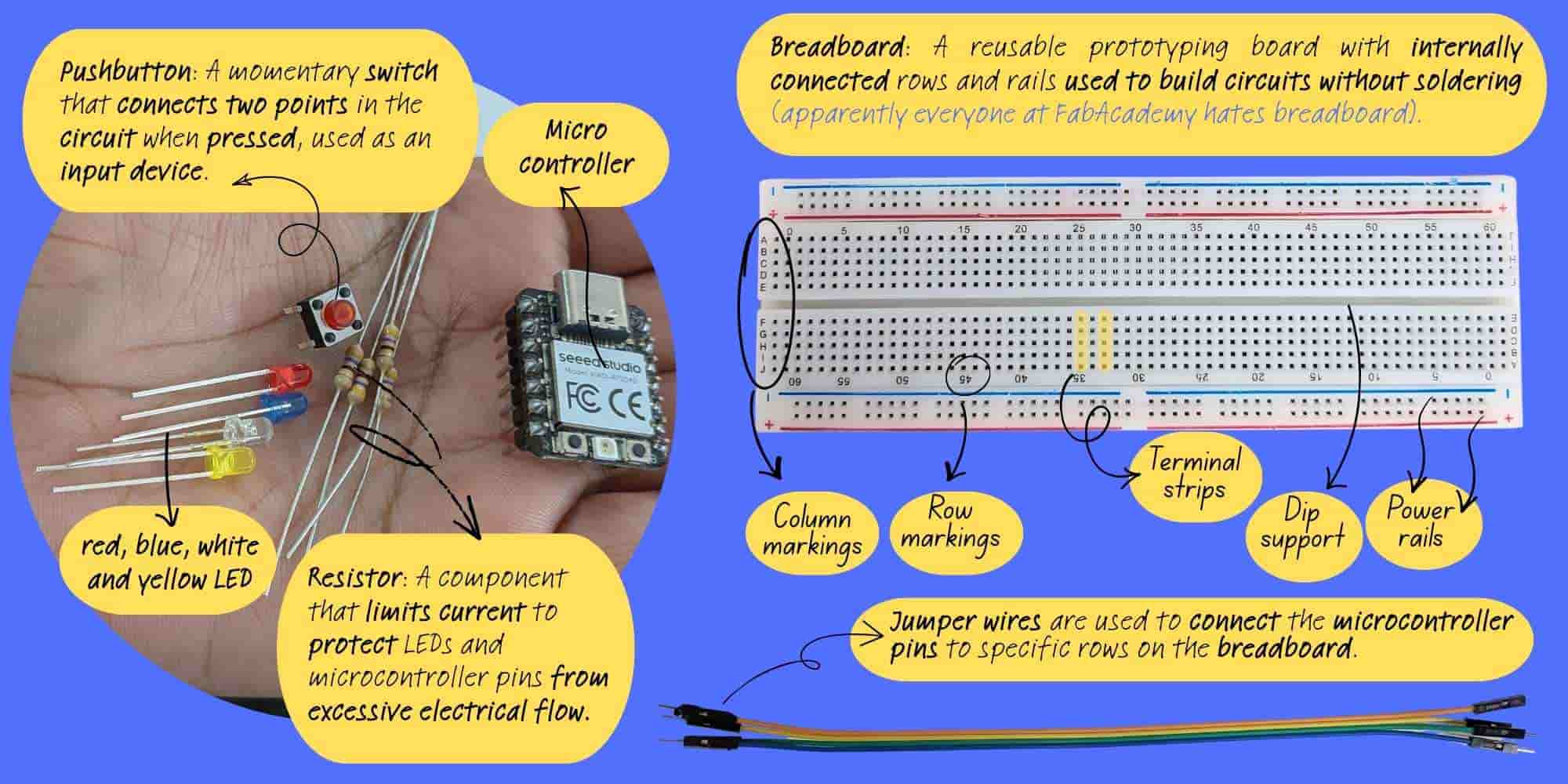

Vocabulary & Concepts I Encountered This Week

The last time I wrote any code was around 12 years ago in school. I never used it again after that. So this week felt strange in two ways: I was excited to finally use coding in a real, physical way, but at the same time I felt like I was starting from zero. On top of that, I have never worked with electronics before. So I wasn’t just revising programming, I was learning how electricity behaves, what resistors do, and why hardware can break if wired incorrectly. Because of that, I needed to understand the vocabulary before I could understand what I was actually doing. Here are the terms that became meaningful to me this week.

Microcontroller

I am working with the XIAO RP2040. Inside it is a microcontroller called RP2040. A microcontroller is basically a small computer on a chip. It has:

GPIO

GPIO stands for General Purpose Input/Output. These are the pins that let the microcontroller interact with the outside world.

void setup()

The void setup() function initializes settings, configures pin modes,

starts libraries, and initializes serial communication. It runs only once

when the board is powered on or reset, preparing the environment for

void loop().

void loop()

The void loop() function executes the main logic continuously.

It runs after setup() completes and repeats endlessly

until the board is powered off or reset.

pinMode()

Before using a pin, I must define its behavior.

pinMode(YELLOW, OUTPUT);

pinMode(BUTTON, INPUT_PULLDOWN);

If not defined correctly, the hardware does not behave as expected. This helped me understand that hardware behavior must be explicitly declared in software.

digitalWrite()

This sends a voltage signal to a pin. I used it to:

- Turn LEDs on

- Turn LEDs off

- Create blinking patterns

Although it appears as a simple function, it actually controls physical voltage on the board.

digitalRead()

This reads the voltage level of a pin. I used it to check whether the button was pressed, which made my project interactive instead of running automatically.

Logic Level (HIGH / LOW)

Digital pins operate using two logic levels:

RP2040 Datasheet Study

This week was my first time reading a microcontroller datasheet. The document is very long and technical, so instead of trying to understand everything, I focused on the parts that were directly connected to my project: GPIO, pin mapping, memory, and boot behaviour.

Overview of the RP2040

From the introduction section, I learned that the RP2040 is the microcontroller chip inside the XIAO board. It has two processor cores, runs up to 133 MHz, and includes 264 KB of SRAM. Programs are stored in external flash memory. Even though I only used simple LED and button control this week, the datasheet shows that the chip supports other features such as SPI, I2C, UART, USB, and analog input.

Why the Chip Is Called RP2040

The naming structure of RP2040 is meaningful; it reflects the chip’s architecture and memory characteristics.

- RP → Raspberry Pi

- 2 → Dual-core processor

- 0 → Cortex-M0+ architecture

- 4 → Based on RAM size calculation

- 0 → Based on non-volatile storage calculation

Key Features (Summary)

The RP2040 includes:

- Dual ARM Cortex-M0+ cores (up to 133 MHz)

- 264 KB SRAM

- 30 GPIO pins

- Dedicated SPI flash interface

- Programmable I/O (PIO)

- 12-bit ADC with temperature sensor

These features make it suitable for embedded systems, signal processing, and general-purpose microcontroller applications.

RP2040 Architecture and Clock Speed

The RP2040 is based on a dual-core ARM Cortex-M0+ architecture. Each core is a 32-bit processor designed for low-power embedded applications. The two cores can operate simultaneously, allowing task separation and improved performance.

The chip runs at a maximum clock speed of 133 MHz, meaning it can execute up to 133 million clock cycles per second. Compared to traditional 8-bit microcontrollers, this provides significantly higher processing capability for real-time control and signal processing tasks.

GPIO and Pin Understanding

The datasheet explains that the RP2040 has 30 GPIO pins (GPIO0–GPIO29). However, the XIAO board does not expose all of them. Only a subset is available as labeled pins like D0, D1, D2, etc. Each GPIO pin can be configured as input or output. This directly relates to my project:

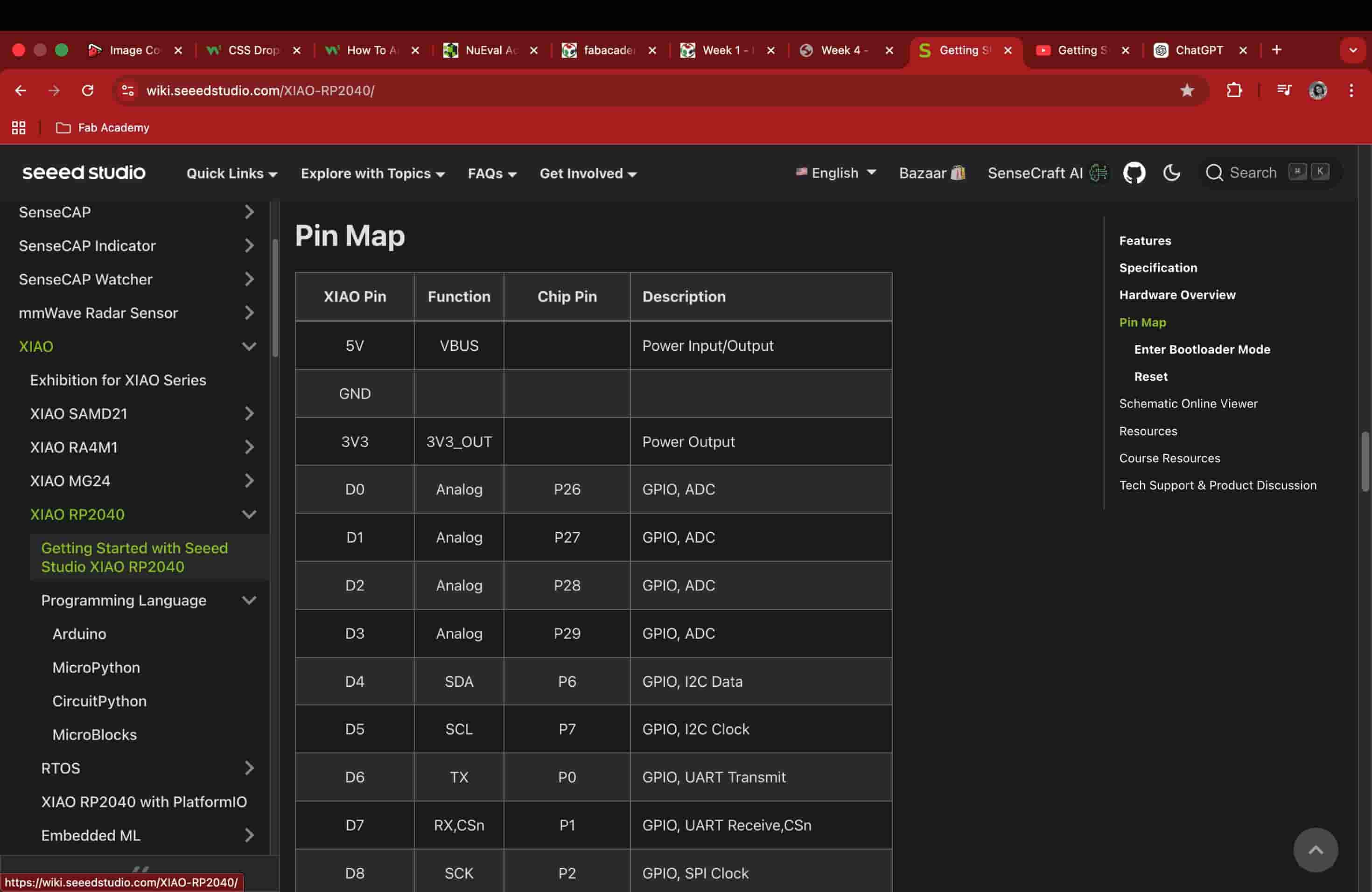

Pin Mapping Between Chip and Board

The datasheet shows internal GPIO numbers, but the XIAO board uses different labels. I had to refer to the XIAO pin map to understand which board pin corresponds to which internal GPIO number. This explains why the default Blink example did not work initially, it was written for a different board configuration.

Memory and Program Storage

From the datasheet summary, I understood that:

- SRAM is used temporarily while the program runs.

- External flash memory stores the program permanently.

- The boot process loads and executes the firmware after power-up.

This helped me understand what actually happens when I upload code and power the board.

Reset and Boot

From the board documentation, I learned that:

- The RESET button restarts the microcontroller.

- The BOOT button allows firmware upload.

Previously, pressing these buttons felt abstract. Now I understand that they trigger hardware-level behaviour inside the chip.

Implementation: From Zero to a Working Input-Output System

This week was my first time building an actual electronic circuit. I had never used a breadboard before. I had never connected an LED physically. I had never used a resistor in real life. At the same time, the last time I wrote code was 12 years ago in school. So this week felt like restarting programming, but now with hardware involved. I decided to begin very small: make one LED blink.

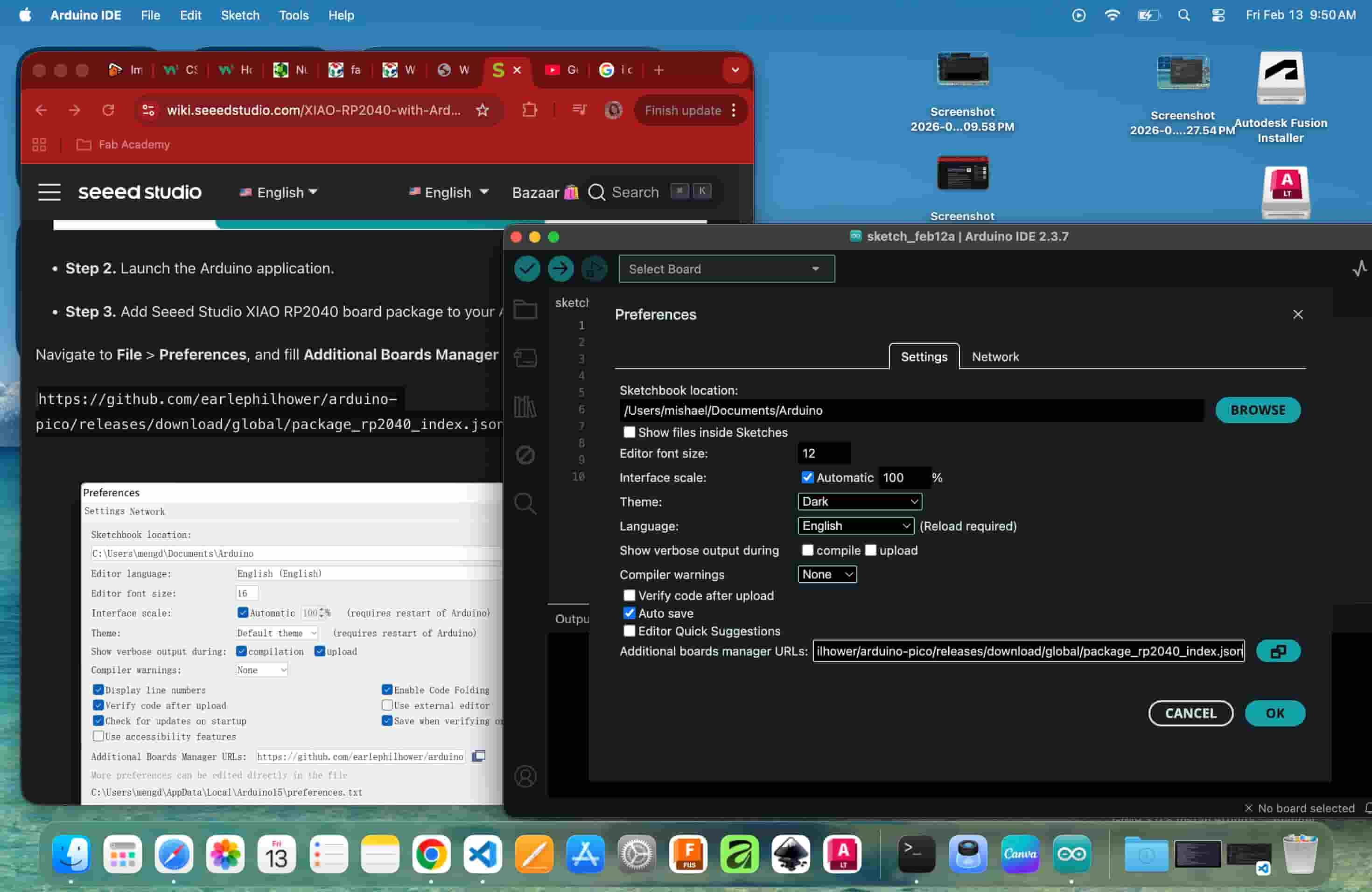

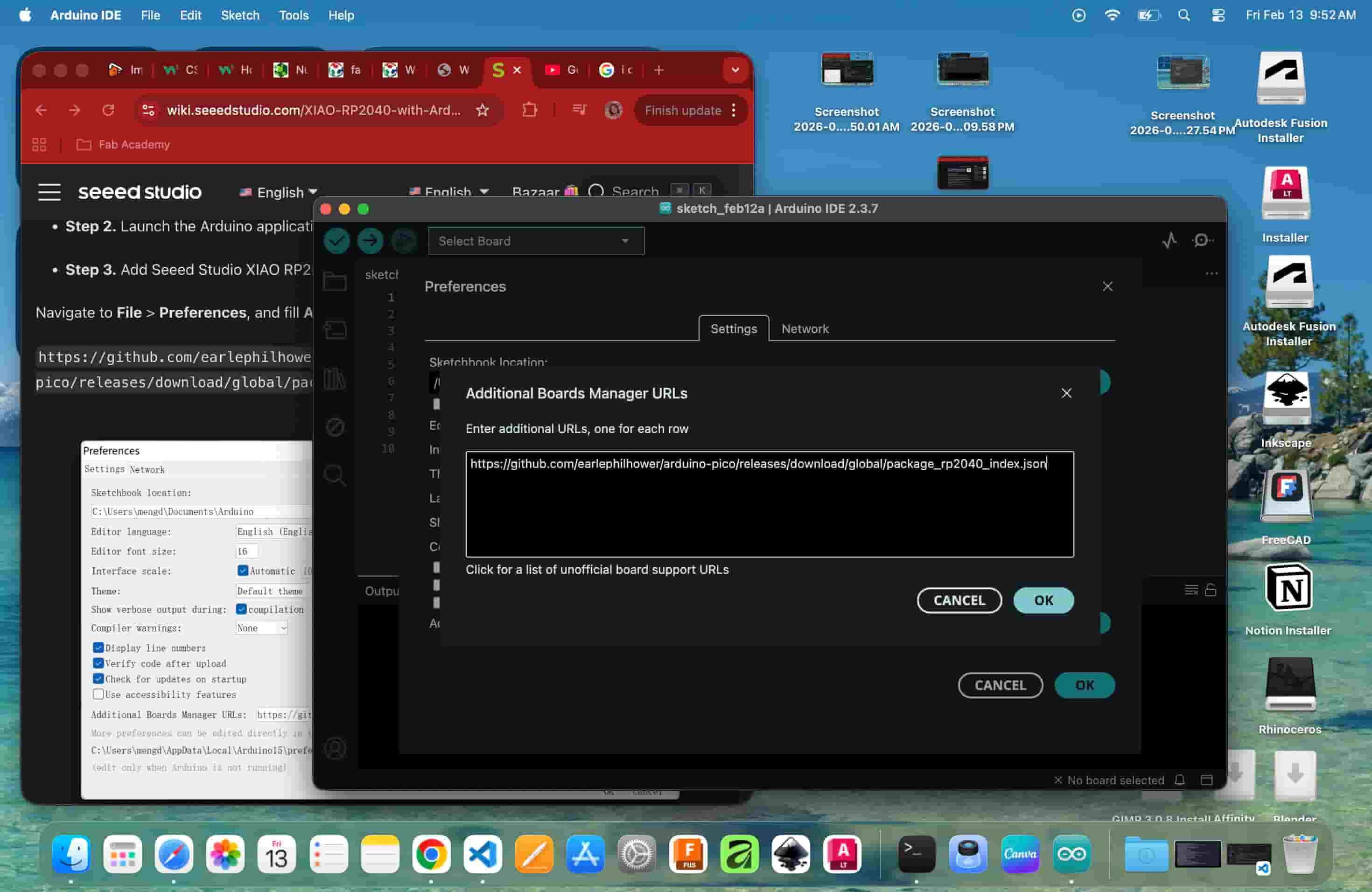

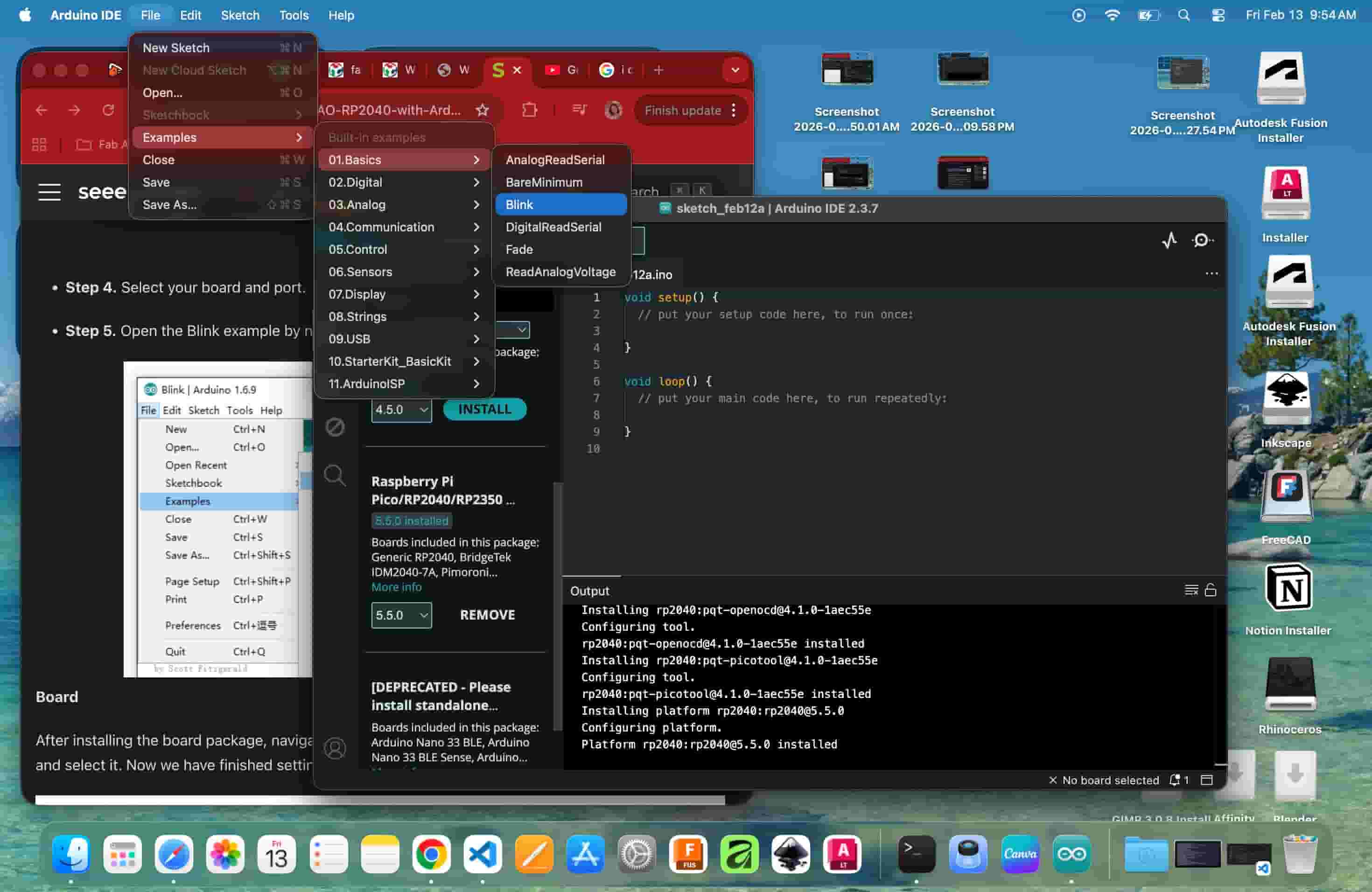

Setting Up the XIAO RP2040

I connected the XIAO RP2040 to my MacBook using a USB-C cable and installed Arduino IDE. The setup was done by following the instruction from https://wiki.seeedstudio.com/. There was one change though, for mac, the preferences is not under the File menu but the Arduino IDE menu. I had a hard time figuring the very first step but the rest were according to the website.

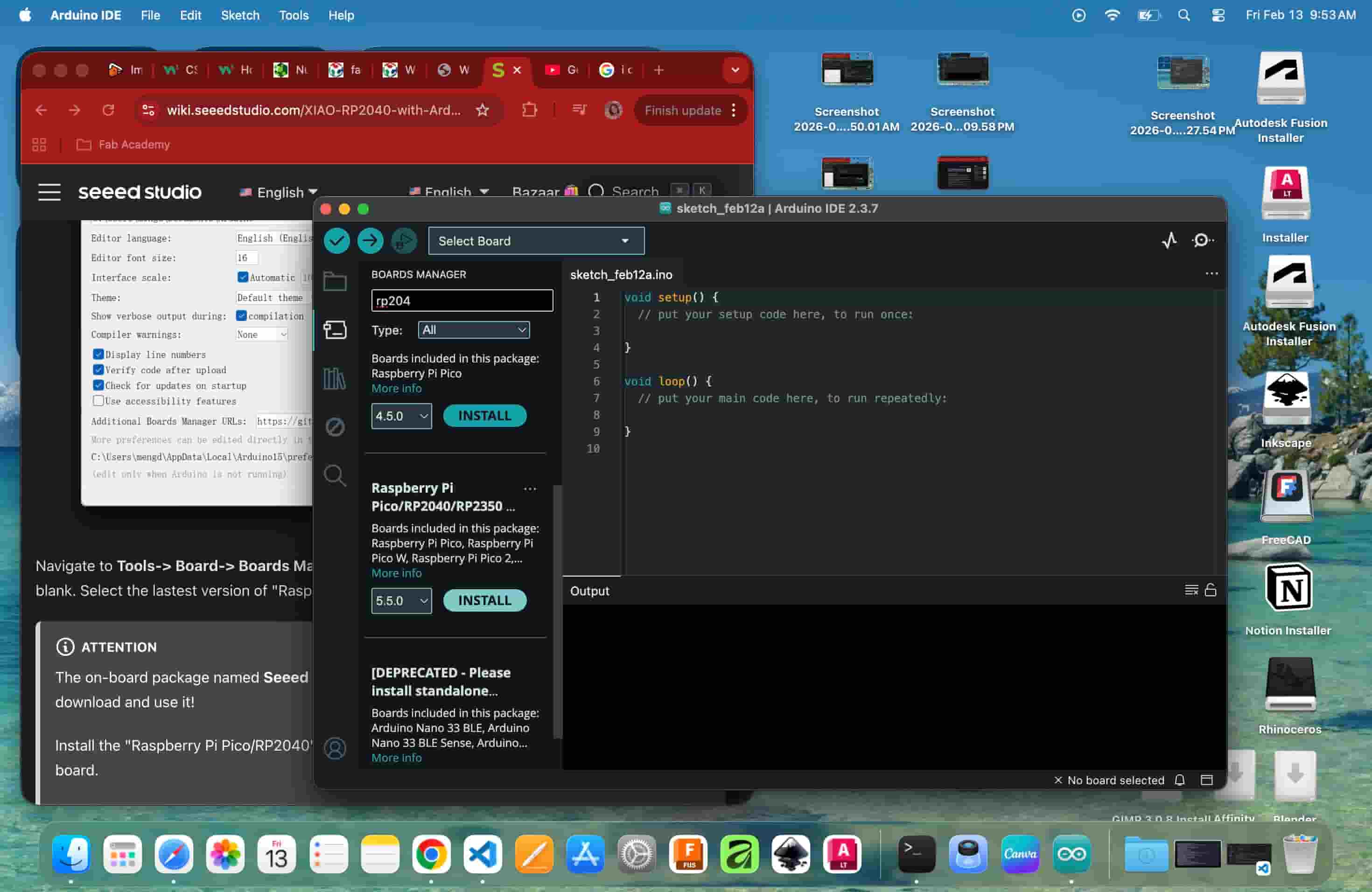

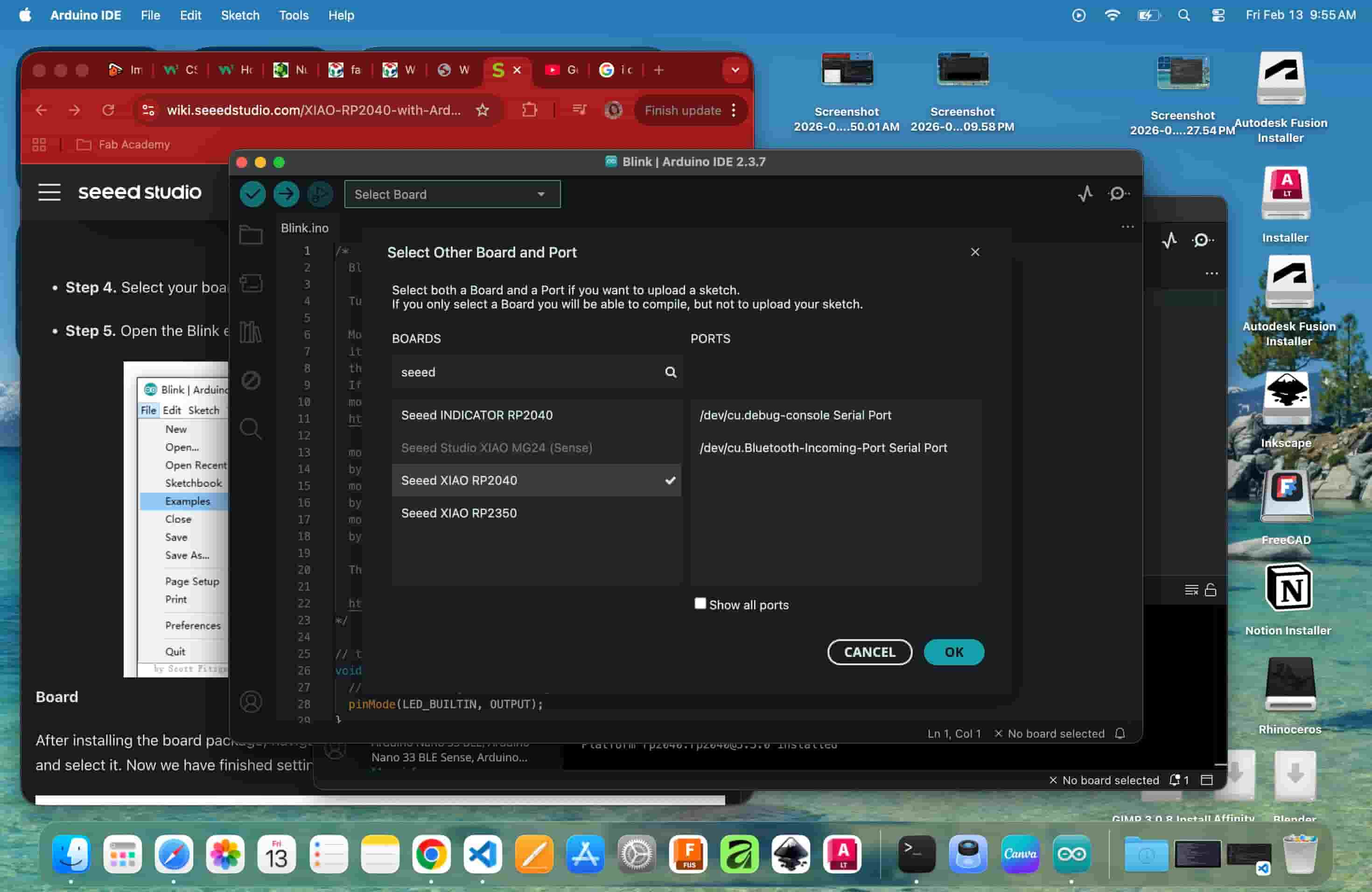

Since this board is not selected by default, I had to:Install the correct board package for RP2040

Select the XIAO RP2040 board

Select the correct port

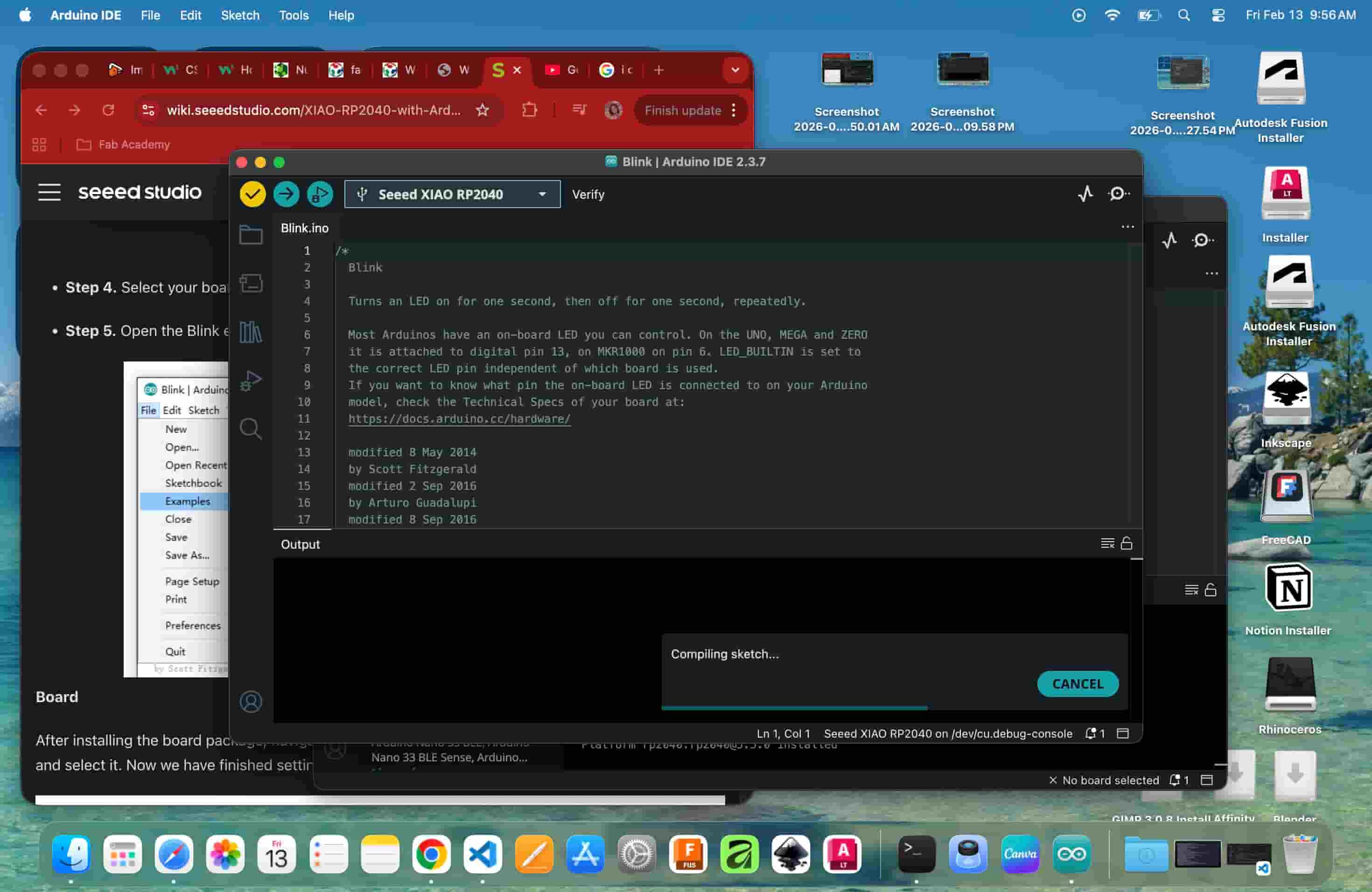

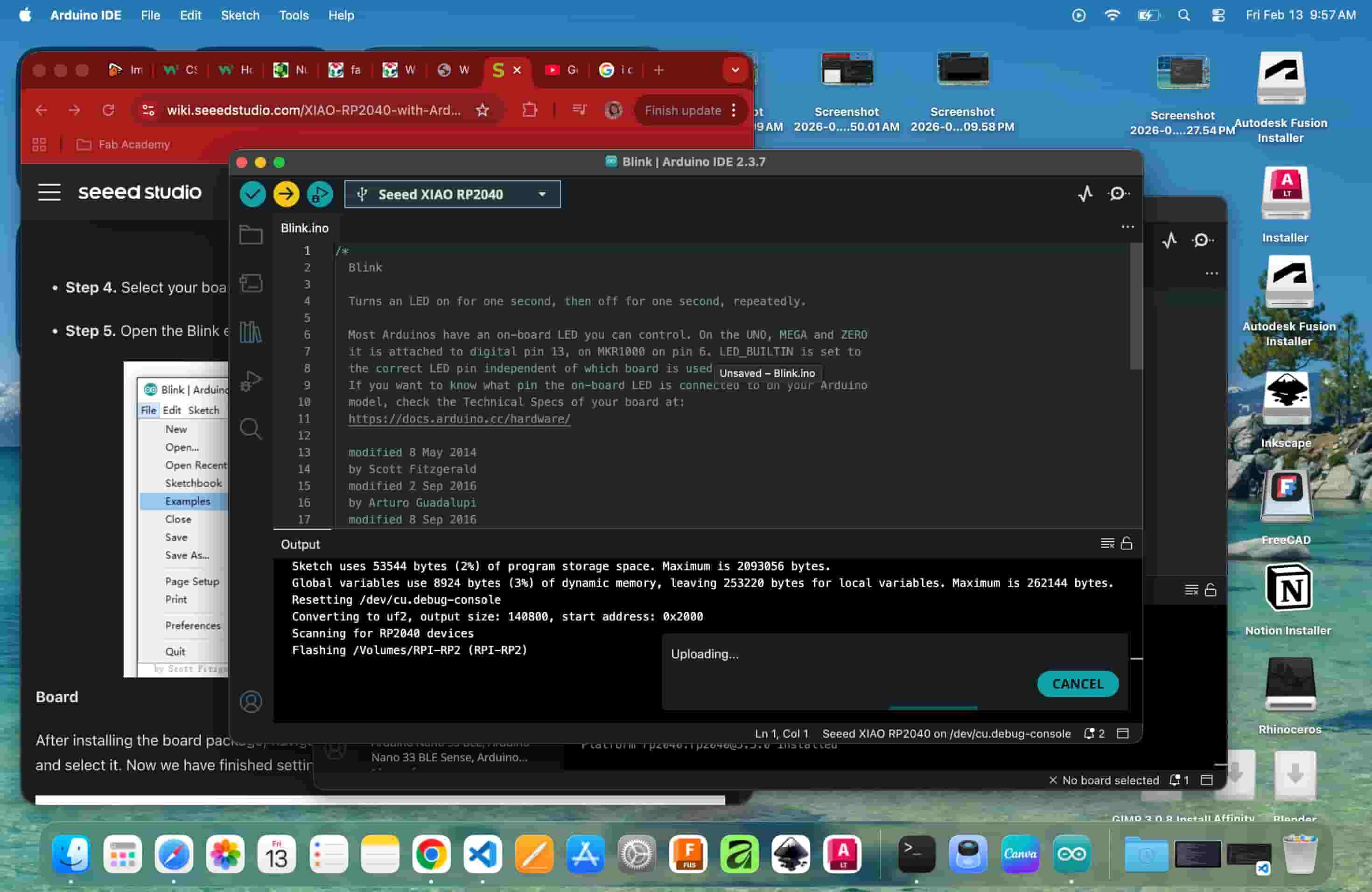

I first tried the default Blink example. It did not work. The example used `LED_BUILTIN`, which does not directly map to the onboard LED pins of the XIAO. After checking the pin map from the wiki and datasheet, I defined the correct RGB LED pin manually:

#define USER_LED_R 17

#define USER_LED_R 17 // Defined USER_LED_R as 17th pin, USER_LED_G as 16 and USER_LED_B as 25 as per the pinmap for the model xiao rp2040 // the setup function runs once when you press reset or power the board void setup() { // initialize digital pin LED_BUILTIN as an output. pinMode(USER_LED_R, OUTPUT); // Replaced LED_BUILTIN with USER_LED_R based on the board we are using } // the loop function runs over and over again forever void loop() { digitalWrite(USER_LED_R, LOW); // turn the LED ON (active-LOW) delay(1000); digitalWrite(USER_LED_R, HIGH); // turn the LED OFF delay(1000); }

This code can create the blink but the other LEDs will be turned on too, so it was rewritten

#define USER_LED_R 17 #define USER_LED_G 16 #define USER_LED_B 25 // Defined RGB LED pins according to the XIAO RP2040 pin map void setup() { // Configure RGB LED pins as output pinMode(USER_LED_R, OUTPUT); pinMode(USER_LED_G, OUTPUT); pinMode(USER_LED_B, OUTPUT); // Turn OFF green and blue channels (RGB LED is active LOW) digitalWrite(USER_LED_G, HIGH); digitalWrite(USER_LED_B, HIGH); } void loop() { // Blink red LED twice digitalWrite(USER_LED_R, LOW); // ON (active LOW) delay(100); digitalWrite(USER_LED_R, HIGH); // OFF delay(300); digitalWrite(USER_LED_R, LOW); // ON delay(100); digitalWrite(USER_LED_R, HIGH); // OFF delay(300); }

In the Arduino IDE, compile (or "Verify") converts human-readable code (sketches) into machine-readable binary files ( ) for the microcontroller, checking for errors, while upload transfers this binary file to the Arduino board via USB, enabling it to execute the instructions.

Understanding the Breadboard

Before connecting external components, I had to understand how the breadboard works. At first it looked like random holes. But I learned:

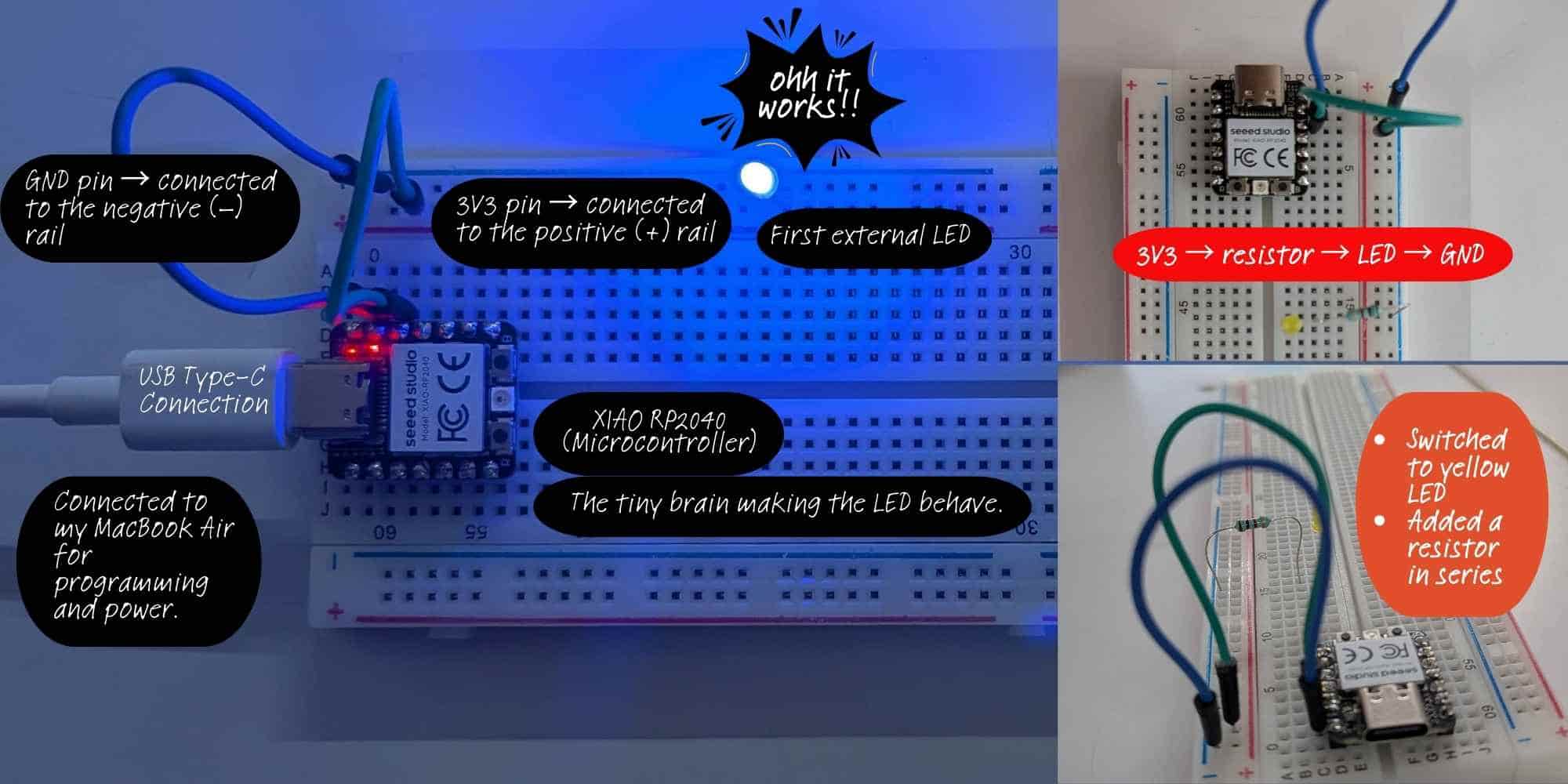

Lighting My First External LED

Next, I connected a single external LED. I learned that an LED has:

In this setup, I powered my first external LED directly using the 3V3 and GND pins of the XIAO RP2040.

#define YELLOW D7 // defined the external LED connected to D7 pin // the setup function runs once when you press reset or power the board void setup() { pinMode(YELLOW, OUTPUT); } // the loop function runs over and over again forever void loop() { digitalWrite(YELLOW, HIGH); // turn the LED on (HIGH is the voltage level) delay(500); digitalWrite(YELLOW, LOW); // turn the LED off by making the voltage LOW delay(500); digitalWrite(YELLOW, HIGH); // turn the LED on (HIGH is the voltage level) delay(500); digitalWrite(YELLOW, LOW); // turn the LED off by making the voltage LOW delay(500); }

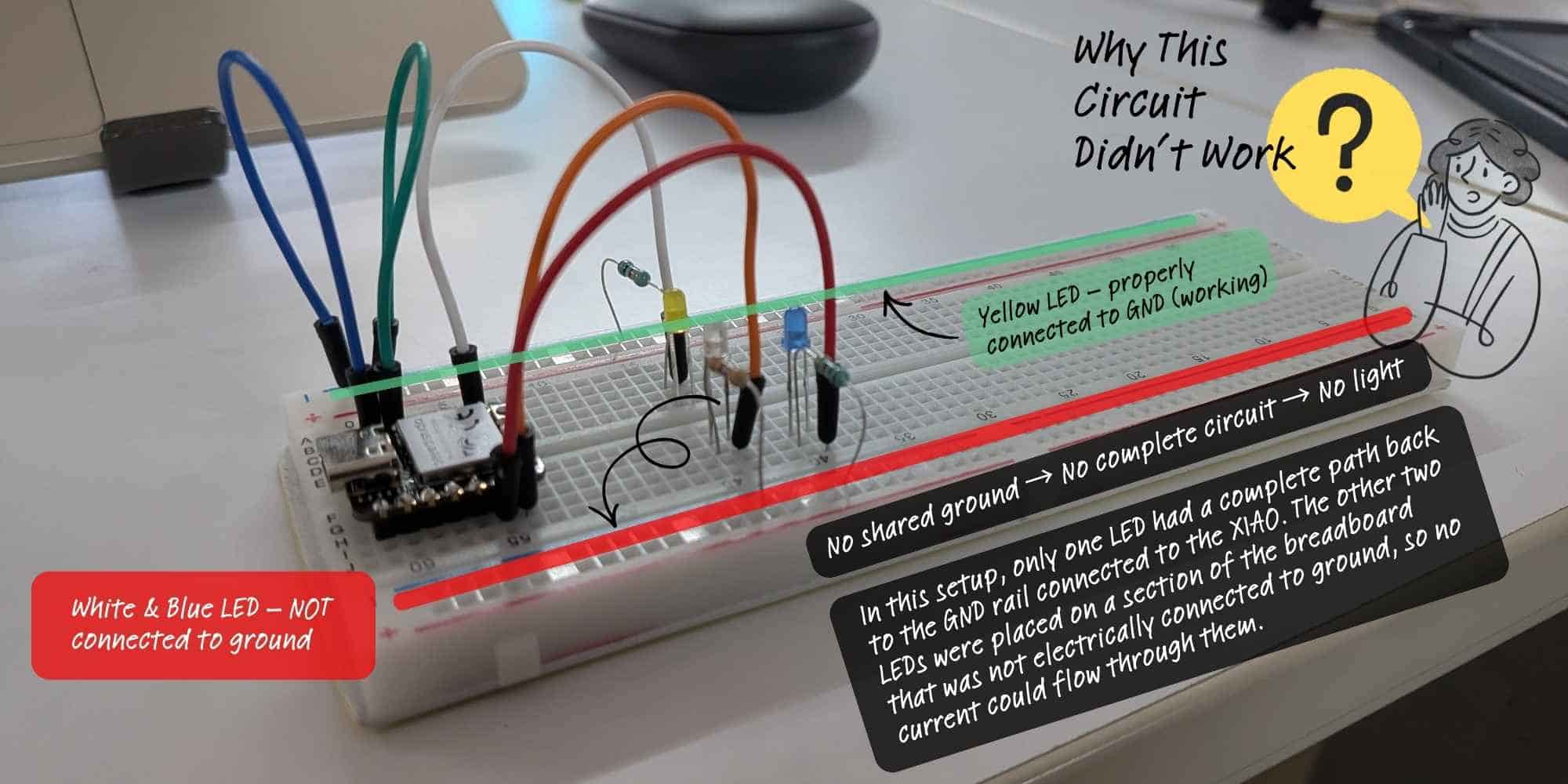

Multiple LEDs and Chase Sequence (Output)

After successfully lighting one LED, I added two more LEDs:

When I moved from lighting a single LED to connecting multiple LEDs for the chase sequence, I assumed I had wired everything correctly because each LED had its own resistor and was connected to a D pin. However, the circuit did not work as expected. The issue was not in the code, it was in the grounding. Only one LED had a proper connection back to the GND rail linked to the XIAO RP2040. The other LEDs were placed on a section of the breadboard that was not electrically connected to the ground line. Even though the wiring looked correct visually, the circuit was incomplete for two of the LEDs, so no current could flow through them. This mistake helped me understand that every component must share a common ground, and that breadboard power rails are not automatically connected across sections.

Once all negative legs were connected to the GND rail, I wrote a chase sequence using digitalWrite() and delay() so that one LED turned on at a time in a loop. This helped me understand timing and sequential output control.

#define YELLOW D7 #define WHITE D6 #define BLUE D5 // the setup function runs once when you press reset or power the board void setup() { // initialize digital pin LED_BUILTIN as an output. pinMode(YELLOW, OUTPUT); pinMode(WHITE, OUTPUT); pinMode(BLUE, OUTPUT); } // the loop function runs over and over again forever void loop() { digitalWrite(YELLOW, HIGH); // turn the LED on (HIGH is the voltage level) digitalWrite(WHITE, LOW); // turn the LED off by making the voltage LOW digitalWrite(BLUE, LOW); // turn the LED on (HIGH is the voltage level) delay(200); digitalWrite(YELLOW, LOW); digitalWrite(WHITE, HIGH); digitalWrite(BLUE, LOW); delay(200); digitalWrite(WHITE, LOW); digitalWrite(BLUE, HIGH); digitalWrite(YELLOW, LOW); delay(200); }

Once I figured out the wiring, I then added one more LED and created a chase loop ina square arrangement

#define YELLOW D7 #define WHITE D6 #define BLUE D5 #define RED D8 #define time 100 // the setup function runs once when you press reset or power the board void setup() { // initialize digital pin LED_BUILTIN as an output. pinMode(YELLOW, OUTPUT); pinMode(WHITE, OUTPUT); pinMode(BLUE, OUTPUT); pinMode(RED, OUTPUT); } // the loop function runs over and over again forever void loop() { digitalWrite(YELLOW, HIGH); // turn the LED on (HIGH is the voltage level) digitalWrite(WHITE, LOW); // turn the LED off by making the voltage LOW digitalWrite(BLUE, LOW); // turn the LED on (HIGH is the voltage level) digitalWrite(RED, LOW); // turn the LED on (HIGH is the voltage level) delay(time); digitalWrite(YELLOW, LOW); digitalWrite(WHITE, HIGH); digitalWrite(BLUE, LOW); digitalWrite(RED, LOW); delay(time); digitalWrite(WHITE, LOW); digitalWrite(BLUE, HIGH); digitalWrite(YELLOW, LOW); digitalWrite(RED, LOW); delay(time); digitalWrite(WHITE, LOW); digitalWrite(BLUE, LOW); digitalWrite(RED, HIGH); digitalWrite(YELLOW, LOW); delay(time); }

Hero Shot

Embedded System

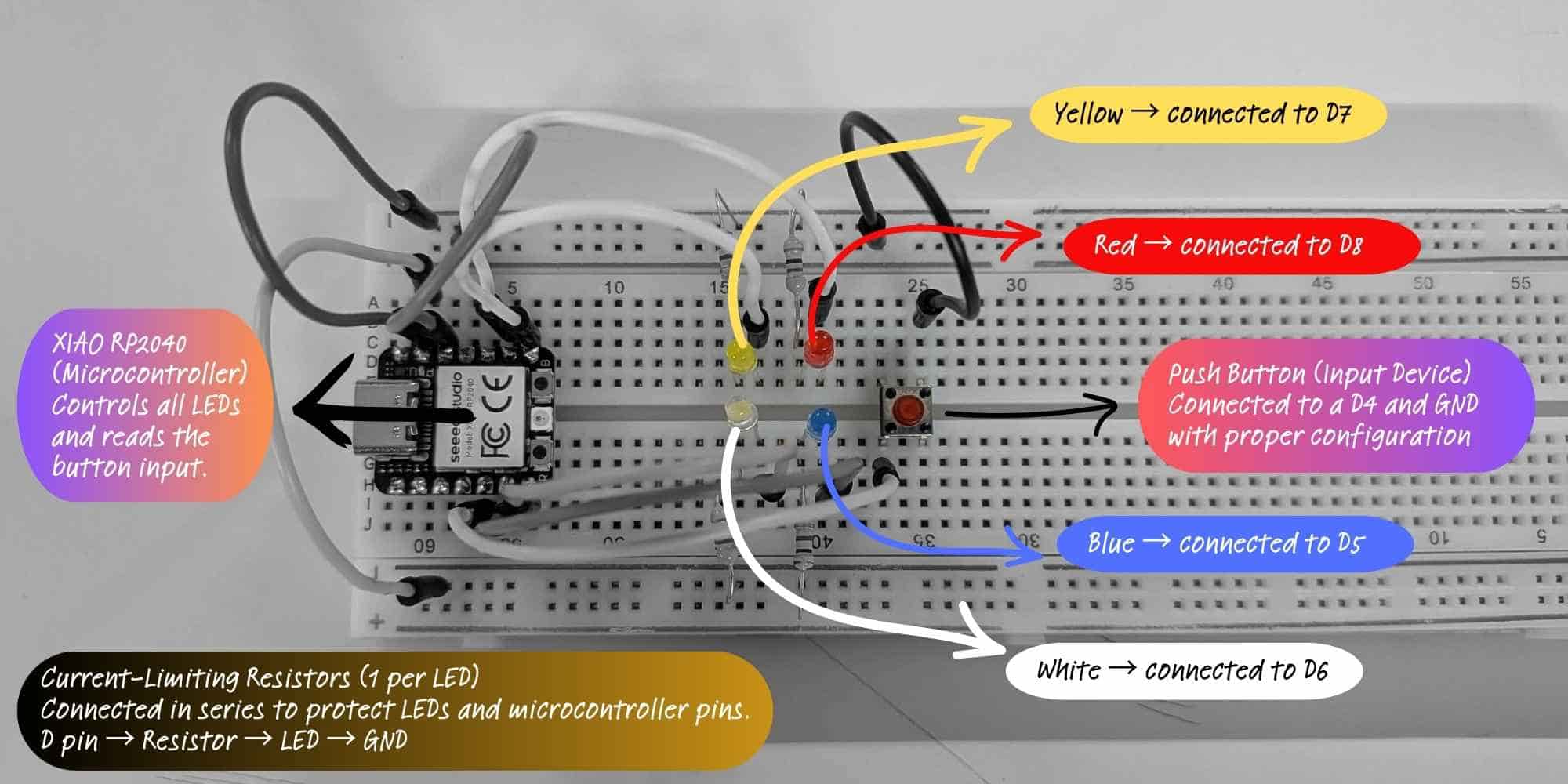

Adding a Push Button for LED Chase (Input & Output Devices)

After working with outputs, I wanted to understand input. I added a push button to the breadboard. The button has four legs but internally works as a switch connecting two sides when pressed. In code:

pinMode(BUTTON, INPUT_PULLDOWN);

Inside loop(), I used:

if (digitalRead(BUTTON) == HIGH)

This was my first complete system combining:

This is the completed circuit after correcting grounding issues. Each LED (yellow, white, blue, red) is connected to a separate D pin on the XIAO RP2040, with an individual current-limiting resistor connected in series. All LEDs share a common ground rail connected to the XIAO’s GND pin. The push button is connected to D4 and GND and configured as an input device in the program. When pressed, it triggers the LED chase sequence. This setup represents a complete input-output embedded system:

#define YELLOW D7 #define WHITE D6 #define BLUE D5 #define RED D8 #define time 100 #define BUTTON D4 // the setup function runs once when you press reset or power the board void setup() { // initialize digital pin LED_BUILTIN as an output. pinMode(YELLOW, OUTPUT); pinMode(WHITE, OUTPUT); pinMode(BLUE, OUTPUT); pinMode(RED, OUTPUT); pinMode(BUTTON, INPUT_PULLDOWN); } // the loop function runs over and over again forever void loop() { if (digitalRead(BUTTON)==HIGH) { chase_4(); //Made a separate function chase_4 to better organize //To set the condition: if pulldown is used, set the condition to high. if pullup is used, set it to low } else { digitalWrite(YELLOW, LOW); // turn the LED on (HIGH is the voltage level) digitalWrite(WHITE, LOW); // turn the LED off by making the voltage LOW digitalWrite(BLUE, LOW); // turn the LED on (HIGH is the voltage level) digitalWrite(RED, LOW); // turn the LED on (HIGH is the voltage level) } } // to run the leds as a ring void chase_4() { digitalWrite(YELLOW, HIGH); digitalWrite(WHITE, LOW); digitalWrite(BLUE, LOW); digitalWrite(RED, LOW); delay(time); digitalWrite(YELLOW, LOW); digitalWrite(WHITE, HIGH); digitalWrite(BLUE, LOW); digitalWrite(RED, LOW); delay(time); digitalWrite(WHITE, LOW); digitalWrite(BLUE, HIGH); digitalWrite(YELLOW, LOW); digitalWrite(RED, LOW); delay(time); digitalWrite(WHITE, LOW); digitalWrite(RED, HIGH); digitalWrite(BLUE, LOW); digitalWrite(YELLOW, LOW); delay(time); }

Learning to use For Loop

During Asia Regional review, Rico told me to use the for loop function to cleanup my button chase code. So I tried learning to do that. I tried chasing diagonal this time, for this I just had to change the order of leds. I used a for loop to control the LEDs sequentially instead of writing repeated code for each one.

Integer and Array Declaration

I used int to store whole numbers, including the LED pin numbers.

int leds[] = {YELLOW, BLUE, WHITE, RED};

int numLeds = 4;

The array leds[] groups all LED pins into one list.

Each LED gets an index number (0–3), which allows the for loop to access them one by one.

The variable numLeds stores the total number of LEDs, making the code easier to modify later.

for (int i = 0; i < numLeds; i++)

{

digitalWrite(leds[i], HIGH);

delay(time);

digitalWrite(leds[i], LOW);

}

The loop starts with i = 0 and increases i by 1 each time (i++) until it reaches the total number of LEDs.

Since the LEDs are stored in an array, the loop automatically selects each LED one by one and turns it ON and OFF.

This makes the code shorter, cleaner, and easier to modify.

// Define names for each LED pin #define YELLOW D9 #define BLUE D8 #define WHITE D6 #define RED D5 // Define button pin #define BUTTON D7 // Time delay between LED changes (in milliseconds) #define time 100 // Store all LED pins inside an array // This lets us control them using a loop int leds[] = {YELLOW, WHITE, BLUE, RED}; // Total number of LEDs in the array int numLeds = 4; void setup() { // Set all LED pins as OUTPUT (they send voltage out) pinMode(YELLOW, OUTPUT); pinMode(WHITE, OUTPUT); pinMode(BLUE, OUTPUT); pinMode(RED, OUTPUT); // Set button as INPUT with internal pulldown resistor // When pressed, reads HIGH // When not pressed, reads LOW pinMode(BUTTON, INPUT_PULLDOWN); } void loop() { // Check if button is pressed if (digitalRead(BUTTON) == HIGH) { // If pressed, run LED chase pattern chase_4(); } else { // If not pressed, turn all LEDs OFF // Loop goes through each LED one by one for (int i = 0; i < numLeds; i++) { // leds[i] selects LED number 0,1,2,3 digitalWrite(leds[i], LOW); } } } // Function to run LEDs one after another void chase_4() { // Loop through each LED for (int i = 0; i < numLeds; i++) { // Turn current LED ON digitalWrite(leds[i], HIGH); // Wait for defined time delay(time); // Turn current LED OFF before moving to next digitalWrite(leds[i], LOW); } }

Reflection:After completing my first embedded system and understanding how the blink and chase sequences worked, something unexpected happened. On my way home that evening, I couldn’t stop noticing all the blinking lights around me, on trucks, buses, traffic signals, signboards, and vehicles on the road. It felt like someone had opened a door in my head that had been locked for 30 years. Although I have always been fascinated by lights like anyone else, I had never thought about them from this perspective. Now I found myself observing the exact timing of blink sequences on vehicles and wondering what kind of code would produce that delay, that rhythm, that pattern. For the first time, I was not just seeing lights, I was seeing logic running inside them.

Embedded Programming: Button-Controlled Serial Output

Continuous Output vs State Change Detection

Initially, I used a simple condition:

if (digitalRead(BUTTON) == LOW) {

Serial.println("OUCH");

delay(200);

}

In this version, the message prints continuously while the button is being held down. Since the loop() function runs repeatedly, the condition remains true as long as the button is pressed, resulting in:

OUCH OUCH OUCH OUCH

This method checks the current level of the button (LOW or HIGH).

Later, I implemented state change detection.

In this exercise, I programmed a push button connected to pin D7 to print a message in the Serial Monitor when everytime the button is pressed.

#define BUTTON D7 int lastState = HIGH; void setup() { pinMode(BUTTON, INPUT_PULLUP); Serial.begin(9600); } void loop() { int currentState = digitalRead(BUTTON); if (lastState == HIGH && currentState == LOW) { Serial.println("Ouch, that hurts!"); } lastState = currentState; }

Hero Shot

Explanation

The button is configured using INPUT_PULLUP, which activates the microcontroller’s internal pull-up resistor. This means:

To avoid printing continuously while the button is held down, I used a state change detection method. The variable lastState stores the previous reading of the button. The variable currentState stores the current reading.

The program checks for a transition from HIGH to LOW, which indicates that the button has just been pressed:

if (lastState == HIGH && currentState == LOW)

When this transition occurs, the message:

Ouch, that hurts!

is printed once.

Finally, lastState is updated at the end of each loop cycle so the program can compare values during the next iteration.

Reflection:This activity looked simple at first, but I spent more time debugging than expected. I learned that even if the code is correct, wrong wiring can completely change the result. Fixing the button orientation and understanding how INPUT_PULLUP works helped me understand the connection between hardware and software more clearly. I also learned how to detect a button press properly instead of printing continuously. This exercise made me more patient while debugging and more confident working with physical components.

Button-Controlled LED Blinking with Toggle Function

This program uses a push button to toggle an LED blinking mode on and off. When the button is pressed, the system detects a rising edge (LOW to HIGH) and switches the blinking state. Each press alternates between enabling and disabling the LED blinking.

The variable blinking controls whether the LED should blink. Instead of using delay() for timing, the program uses millis() to create a non-blocking 500 ms interval. This allows the system to continuously check the button state while managing the LED timing simultaneously.

Key concepts demonstrated:

#define LED_PIN D8 #define BUTTON_PIN D7 bool blinking = false; bool lastButtonState = LOW; // Default state is LOW with pull-down bool ledState = LOW; unsigned long previousMillis = 0; const long interval = 500; void setup() { pinMode(LED_PIN, OUTPUT); pinMode(BUTTON_PIN, INPUT_PULLDOWN); // Internal pull-down enabled Serial.begin(9600); } void loop() { bool currentButtonState = digitalRead(BUTTON_PIN); // Detect rising edge (LOW → HIGH) if (lastButtonState == LOW && currentButtonState == HIGH) { blinking = !blinking; // Toggle blinking mode if (blinking) { Serial.println("LED Blinking: ON"); } else { Serial.println("LED Blinking: OFF"); digitalWrite(LED_PIN, LOW); ledState = LOW; } delay(50); // debounce } lastButtonState = currentButtonState; if (blinking) { unsigned long currentMillis = millis(); if (currentMillis - previousMillis >= interval) { previousMillis = currentMillis; ledState = !ledState; digitalWrite(LED_PIN, ledState); } } }

Seeed Studio XIAO RP2040 with MicroPython

Introduction to MicroPython

MicroPython is a version of Python made for microcontrollers. It allows us to write simple Python code and run it directly on small boards like the Seeed Studio XIAO RP2040.

Toolchain Setup

To program the board, I needed an editor that supports MicroPython. For this, I downloaded Thonny IDE.

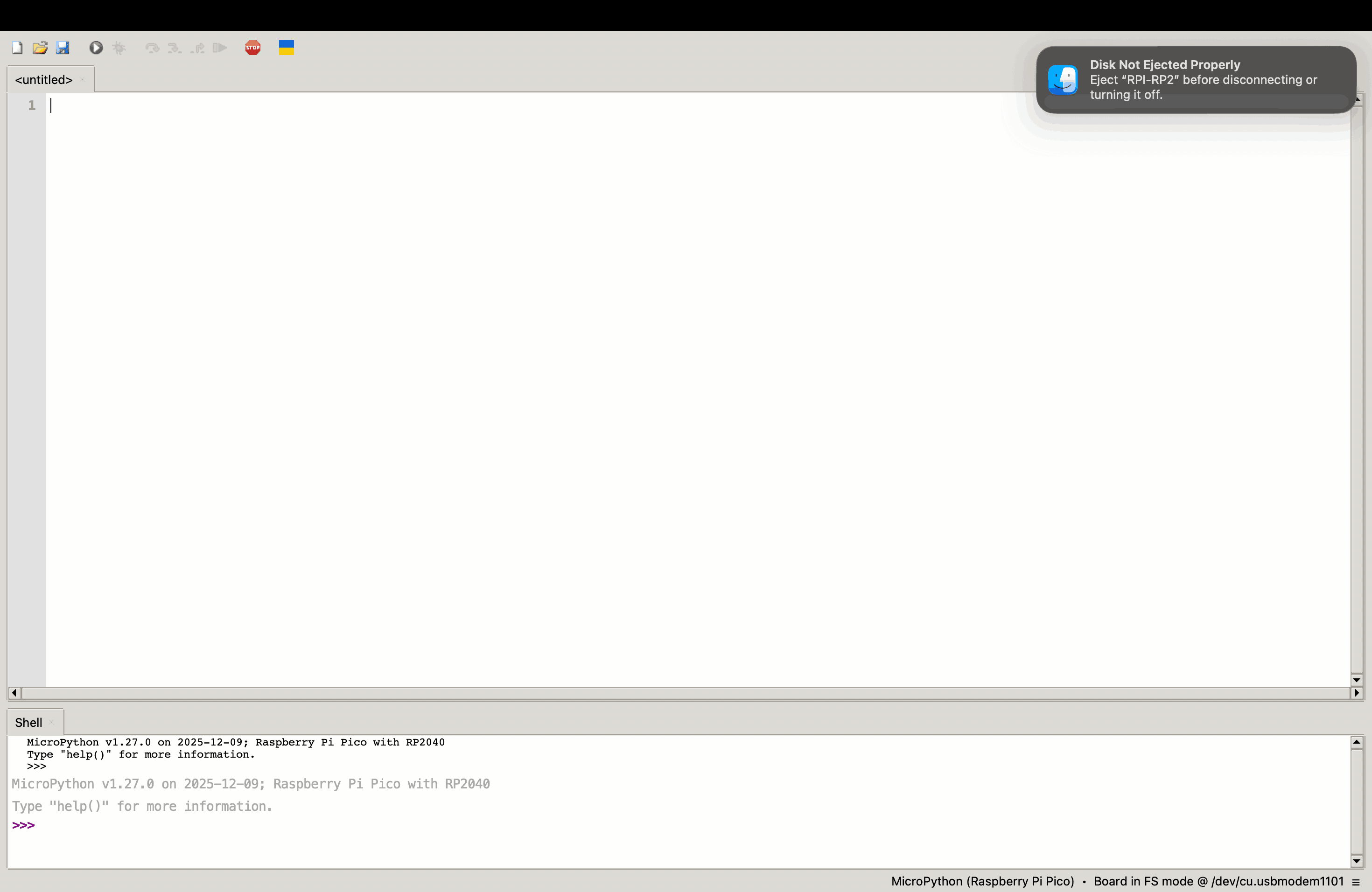

After installing and opening Thonny, I first configured the interpreter. I went to Tools → Options → Interpreter and selected MicroPython (Raspberry Pi Pico) as the interpreter, with the port set to “Try to detect automatically.” This step told Thonny that I was working with a MicroPython-based RP2040 board.

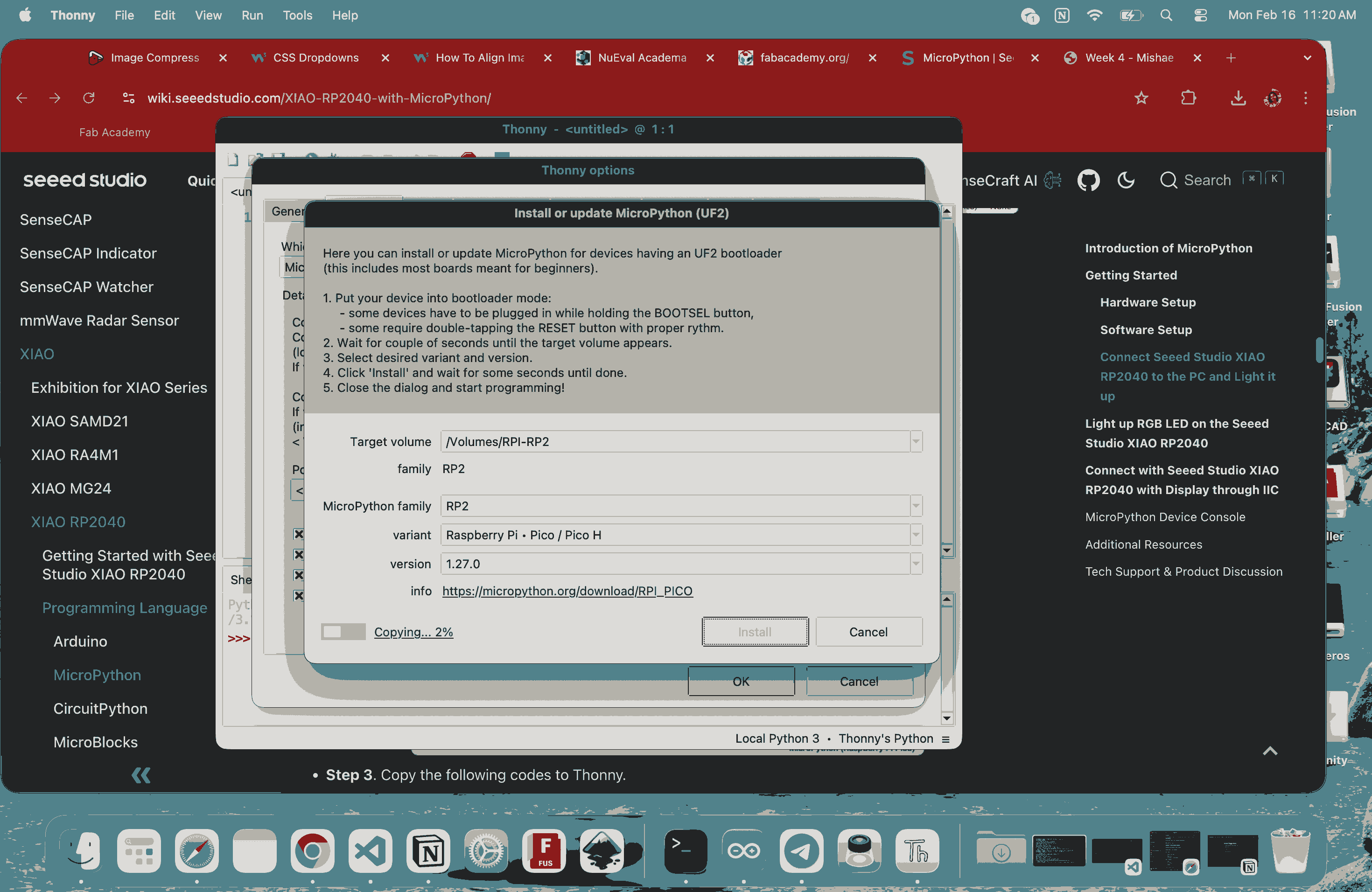

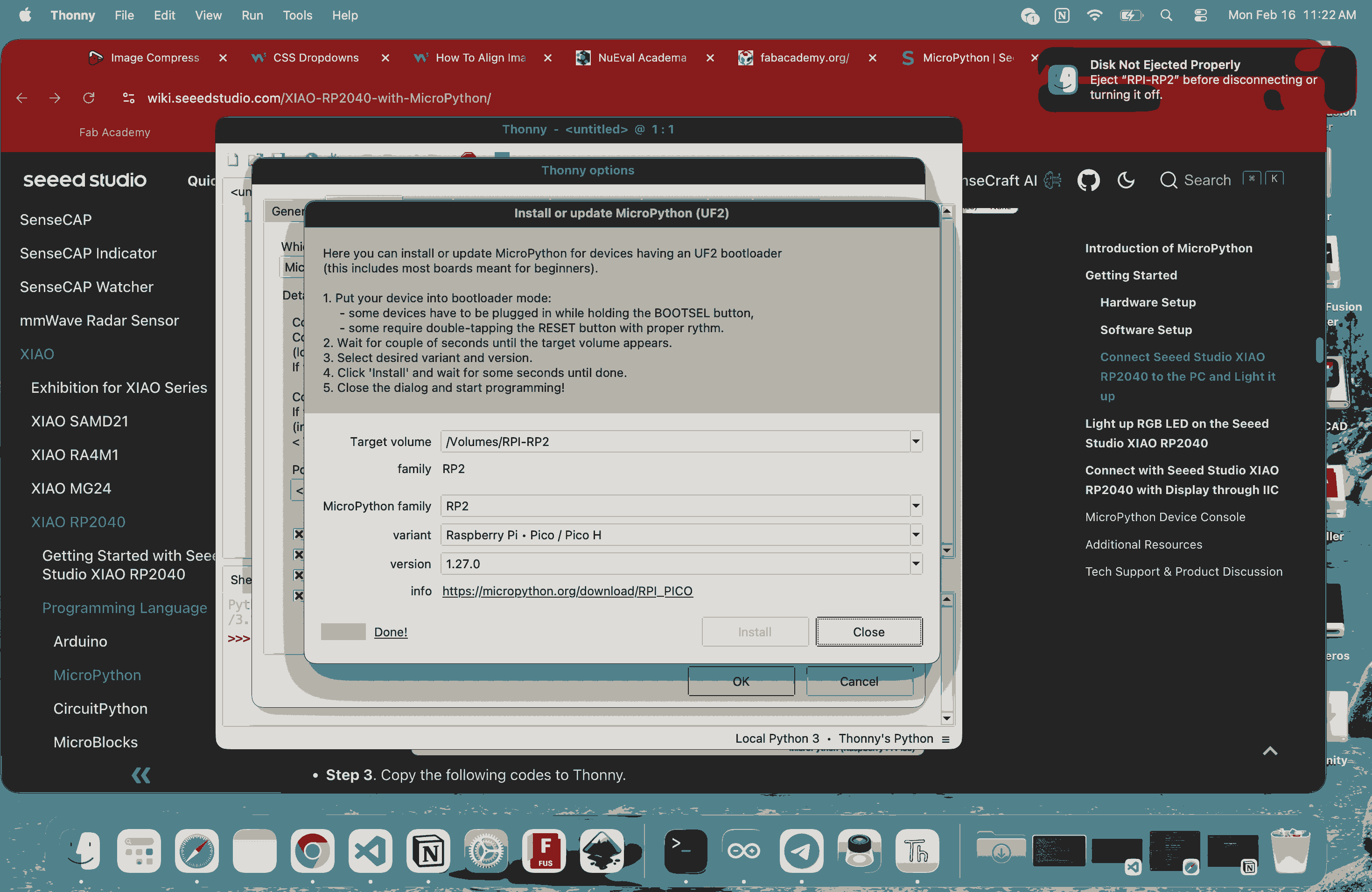

Next, I installed the MicroPython firmware onto the board. To do this, I pressed and held the BOOT button on the XIAO RP2040 and connected it to my computer. The board appeared as an RPI-RP2 drive. In Thonny, I clicked on “Install or Update MicroPython,” kept the default version, and clicked Install. This successfully flashed the MicroPython firmware onto the board.

After the firmware installation, I used the simple LED blinking test program from wiki seeed studio in Thonny and clicked Run. When prompted, I saved the file either to “This Computer” or directly to “Raspberry Pi Pico.” Once executed, the onboard LED started blinking and the counter value printed in the Shell. This confirmed that the board was properly connected, the firmware was correctly installed, and the toolchain was functioning as expected.

from machine import Pin, Timer led = Pin(25, Pin.OUT) Counter = 0 Fun_Num = 0 def fun(tim): global Counter Counter = Counter + 1 print(Counter) led.value(Counter%2) tim = Timer(-1) tim.init(period=1000, mode=Timer.PERIODIC, callback=fun)

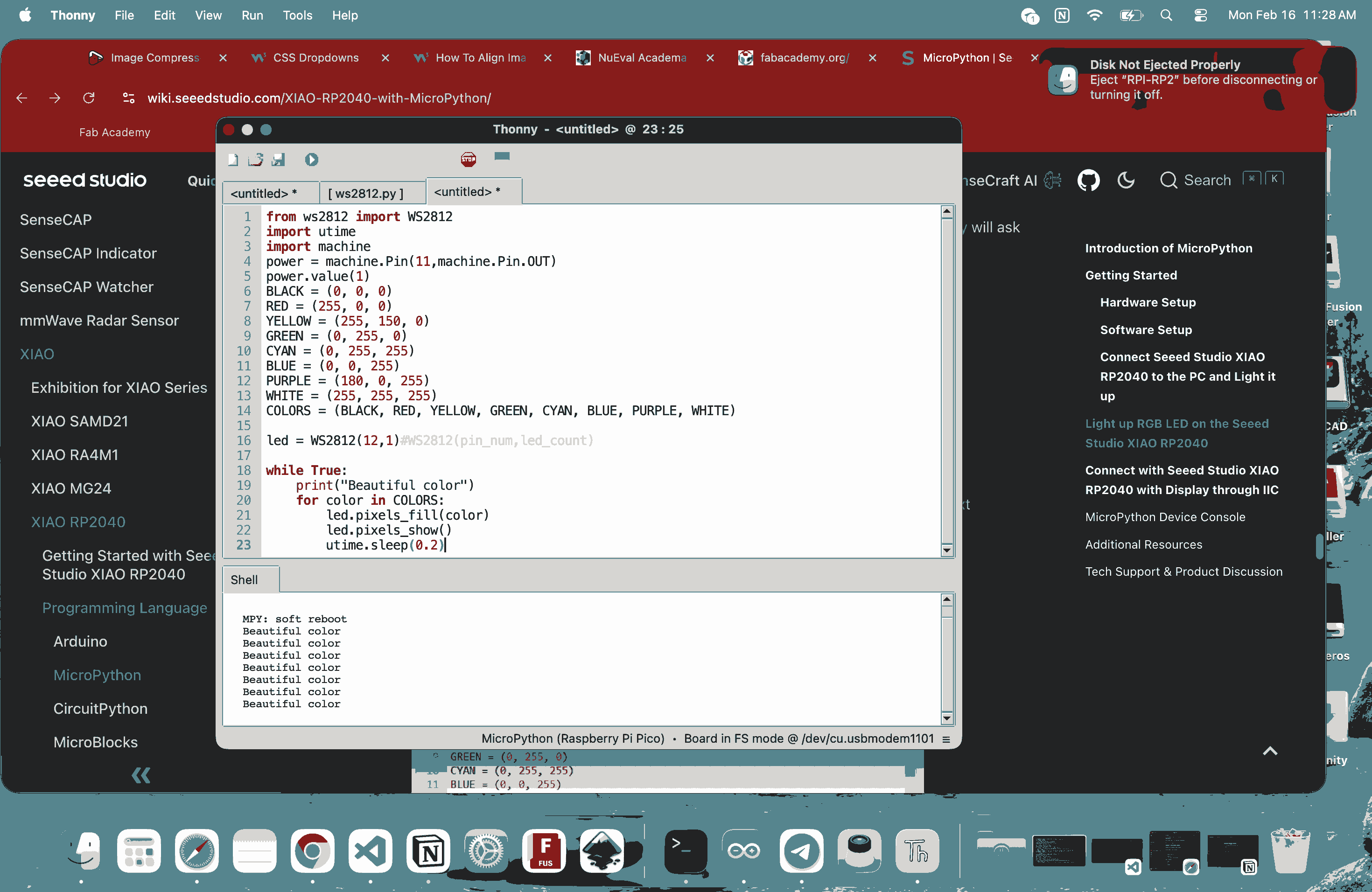

To control the RGB LED, I added an external library. I downloaded the ws2812.py file, opened it in Thonny, and saved it directly to the Raspberry Pi Pico. I made sure the file name was exactly ws2812.py, since any change in the name would prevent it from working. After that, I used the code from wiki seeed studio for the RGB LED program and ran it. The LED cycled through different colors, and the corresponding output was visible in the Shell.

from ws2812 import WS2812 import utime import machine power = machine.Pin(11,machine.Pin.OUT) power.value(1) BLACK = (0, 0, 0) RED = (255, 0, 0) YELLOW = (255, 150, 0) GREEN = (0, 255, 0) CYAN = (0, 255, 255) BLUE = (0, 0, 255) PURPLE = (180, 0, 255) WHITE = (255, 255, 255) COLORS = (BLACK, RED, YELLOW, GREEN, CYAN, BLUE, PURPLE, WHITE) led = WS2812(12,1)#WS2812(pin_num,led_count) while True: print("Beautiful color") for color in COLORS: led.pixels_fill(color) led.pixels_show() utime.sleep(0.2)

Overall, my workflow was straightforward: I downloaded and installed Thonny IDE, used it to install the MicroPython firmware on the XIAO RP2040, and then uploaded and ran the sample codes provided on the Seeed Studio wiki page for setting up Thonny with the XIAO RP2040. I did not write the programs myself at this stage; I used the official example codes to test the setup. I monitored the output through Thonny’s Shell and added the required external library directly to the board. This process confirmed that the board was properly configured and ready for programming using MicroPython.

Reflection

This week was important because it forced me to connect programming with physical systems. I realized that every line of code directly controls voltage on a real pin, HIGH and LOW are actual electrical states, not abstract values. Hardware does not forgive mistakes: wrong wiring, missing resistors, or incorrect pin numbers immediately cause failure. Unlike screen-based programming, both logic and physical connections must work together. I also worked with two different toolchains. One was the Arduino-based workflow, where code is compiled and uploaded as firmware. The other was the MicroPython workflow using Thonny, where I installed firmware separately and then ran scripts directly on the board. Arduino felt more rigid and structured, while MicroPython felt more interactive because I could run and test code quickly through the Shell. For the MicroPython setup, I used the official sample codes from the Seeed Studio wiki to verify that everything was working. I began the week unsure and slightly overwhelmed. By the end, I had