Modeling and Cutting a Brutalist Construction Kit

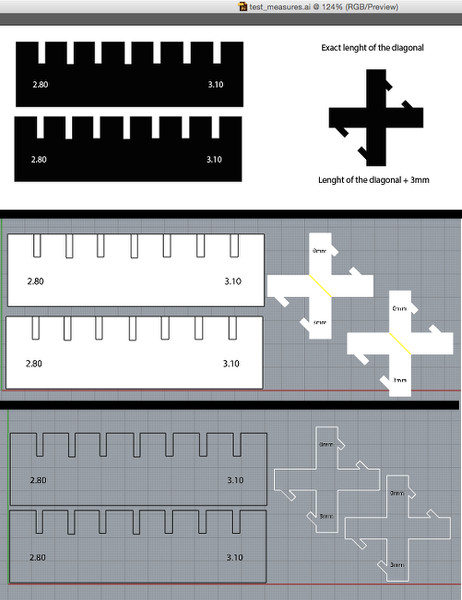

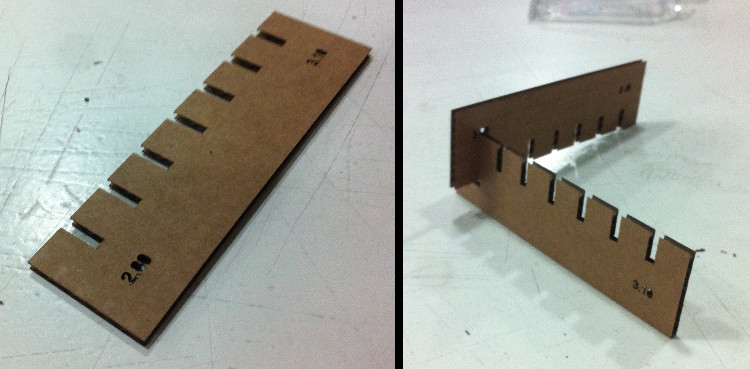

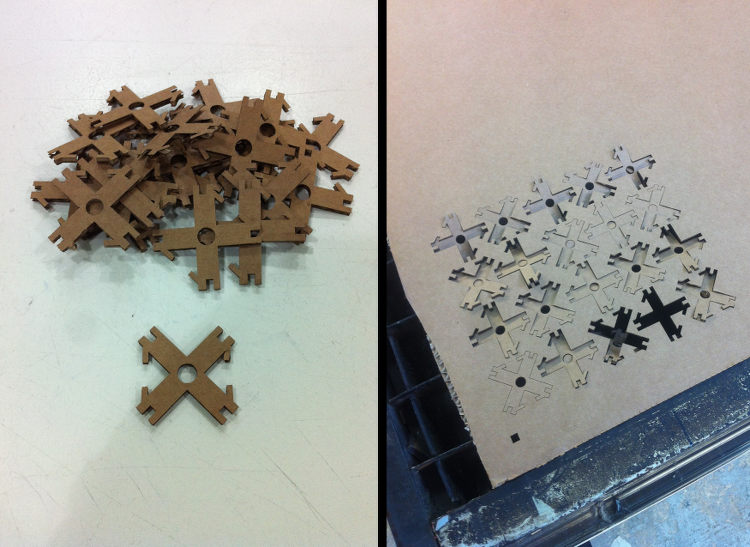

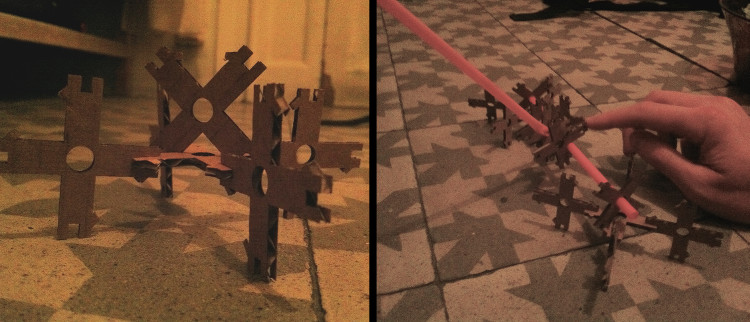

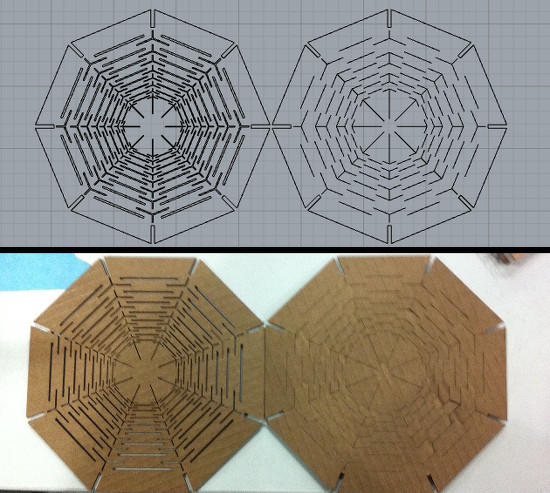

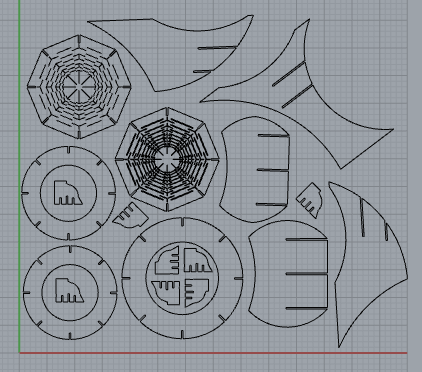

This week started off with Neil’s invitation to first design a construction kit before building anything else and Ferdinand’s emphasis on the importance of testing the material before designing anything else. I therefore decided to start by drawing 1. a little measure tool to evaluate the ideal size of the gaps used to imbricate two pieces together and 2. a first draft of my construction kit piece. Regarding the latter, I decided to take Neil’s invitation quite literally and tried to imagine a single piece that could allow for as many combinations as possible. In my case, my piece could attach itself to another one both linearly and perpendicularly, as well as rotate around and attach itself to a straw.

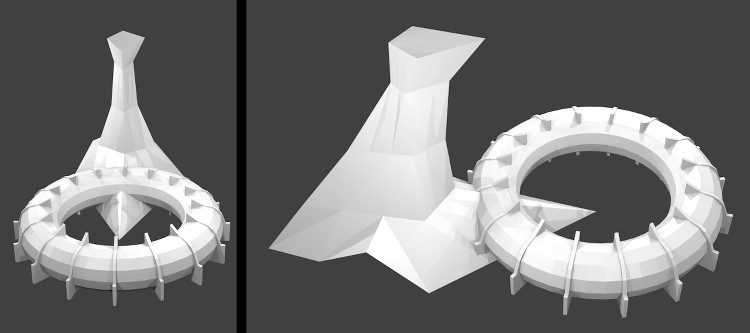

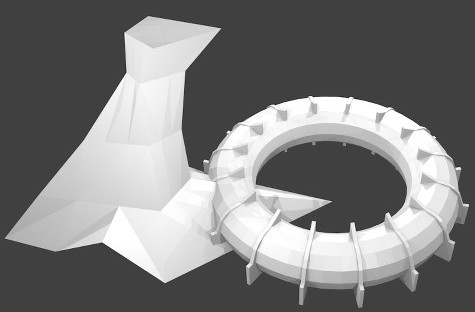

After having completed this first exercise, I decided to do a little homage to one of Montreal’s greatest pieces of brutalist architecture – its Olympic stadium. Of course, its look is not as ‘brutal’ as the Londoner tower blocks that pretty much sum up this movement’s legacy for me – as playfully illustrated by these small buildings kits – but Montreal’s Olympic stadium has become for Montrealers a powerful symbol of the city’s often aggressive architecture. Yet, some of them – including myself – ended up liking it, and now proudly present Montreal as the most beautiful, ugly city there is.

The piece itself wasn’t too hard to design per se – even though making precise measurements in three dimensions made me realized that I really don’t get ‘space’ – but sure was time-consuming. I first tried to directly draw everything in 2D, but quickly realized that I couldn’t get very far with a general visualization first. In the end, I did accumulate a fair amount of drafts in various formats – struggling first with the tower, then spending ages trying to design a satisfactorily flexible roof – but nonetheless ended up with a decent result (‘learning experience’-wise, as opposed to ‘pretty enough to make one’s mother proud’-wise).

See below for all the details/for each step.

- Week: 03

- Subject: Computer-Aided Cutting

- Tools: Rhino, Blender & Illustrator

- Objective: Designing and building the basic pieces of a construction kit, and then develop any other project tackling the possibilities afforded by computer-controlled cutting

- Files: Click here