Embodied Data, Datafied Bodies: 3D Printing and Scanning

Part I: 3D printing

I anticipated this week’s topic – 3D printing– with a mix of curiosity and skepticism. This technics, without denying its actual potential, has evolved into a quite annoying buzzword standing for pretty much everything and its opposite, and I ended up growing tired of all these messianic speeches à la Ted Talk forecasting a world where we will print at home our own consumer goods, machines, houses, organs, food as well as other 3D printers printing each other ad nauseam. This is why – in a weird way – I was agreeably surprised to discover behind these promises a capricious machine full of limits and constrains.

Far from being the magical black box translating pure data in pure matter as it is often caricatured into, 3D printing – from its material constraints to its materials’ – is not simply a finality but a process that must be considered from the very beginning of the design of what will be printed. Wall thickness, filling, hangouts, angles… 3D printing obeys to the most basic physical laws of its material and one must necessarily consider its method of layering in all its subtlety to really tackle the specificities of this medium. 3D printing might indeed convey most of the possibilities that its advocates highlight, but only if it is engaged in its own terms rather than some new all encompassing technology encompassing and displacing all its predecessors and contemporaries.

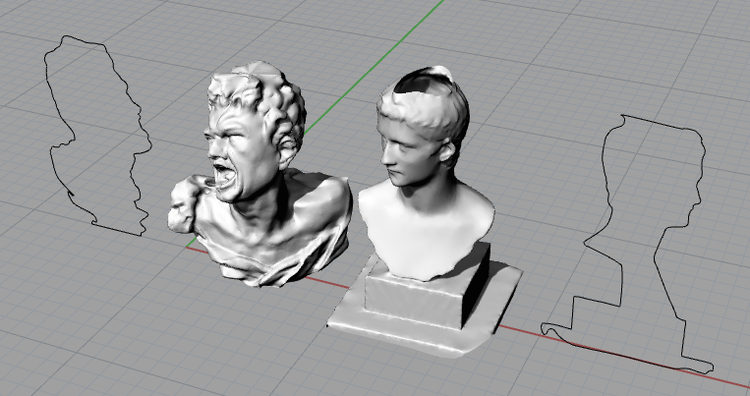

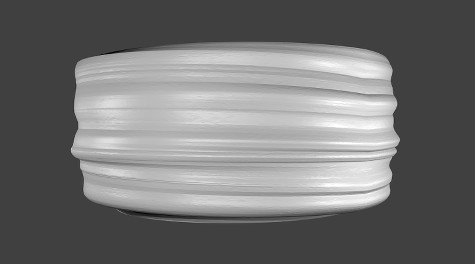

Bref – enough Ted Talk bashing. To explore this means, we were invited to design and print an object that couldn’t be made substractively i.e. in parts to be assembled. To do so, I wanted to stay away from static designs and gave myself as a restriction that my project would have to use the possibilities afforded by 3D printing to emphasize some idea of motion, transformation or expressivity. After a while, I stumbled upon 3D scans from sculptures exposed at the MET museum and extracted the profile of two busts – one with the stoic figure of emperor Gaius and another immortalizing the tormented figure of a screaming martyr – to build a simple, circular object materializing the transition between the two.

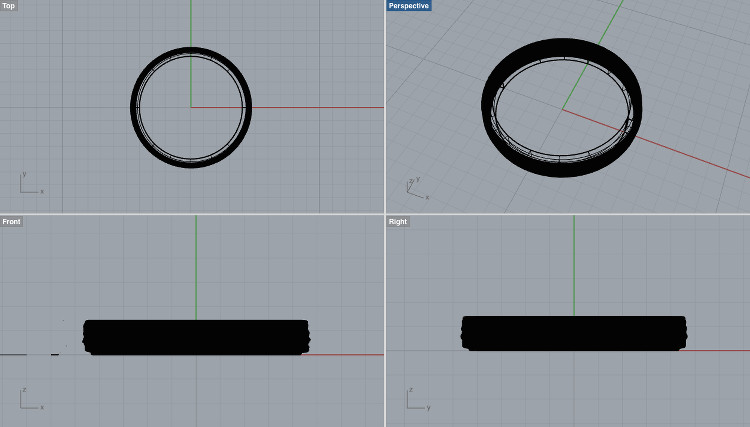

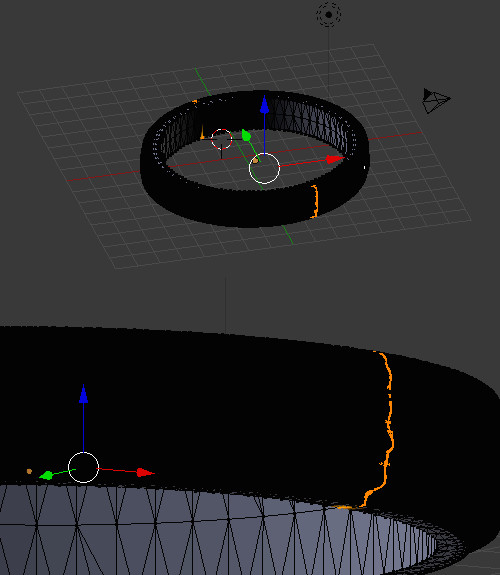

Before printing the object (i.e. monopolizing the MakerBot for hours and wasting a few decades of euros worth of material), I made a quick visualization on Maya to see how the transition between the two faces would look like:

Spinning Janus from Theo L. Richer on Vimeo.

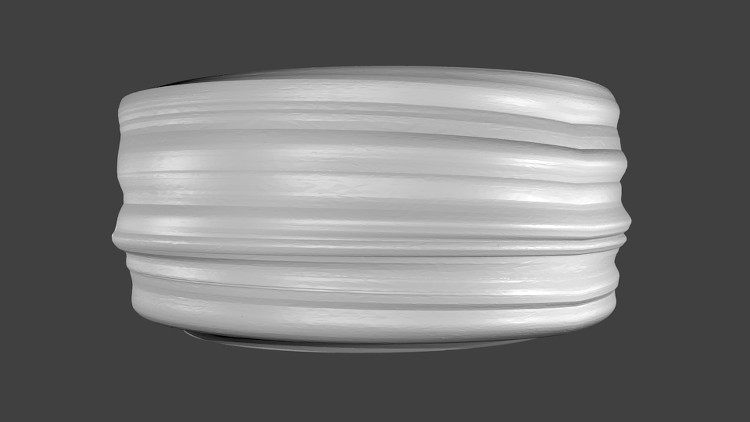

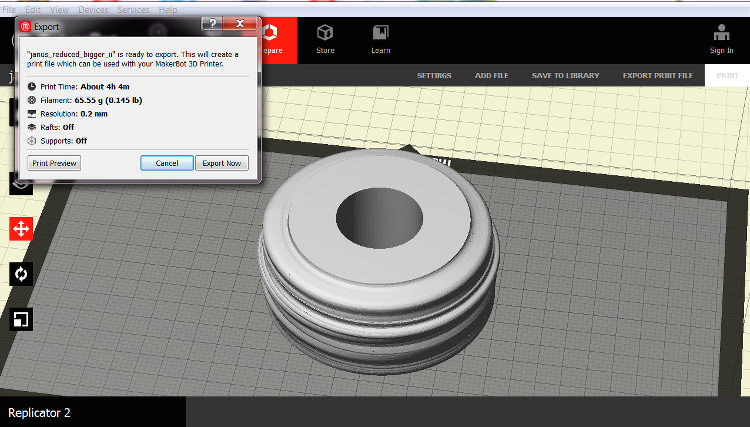

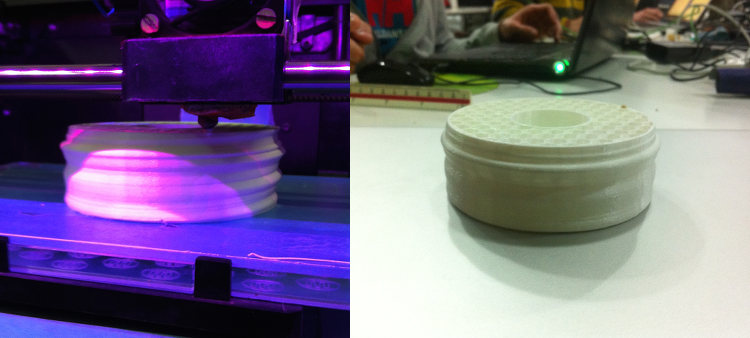

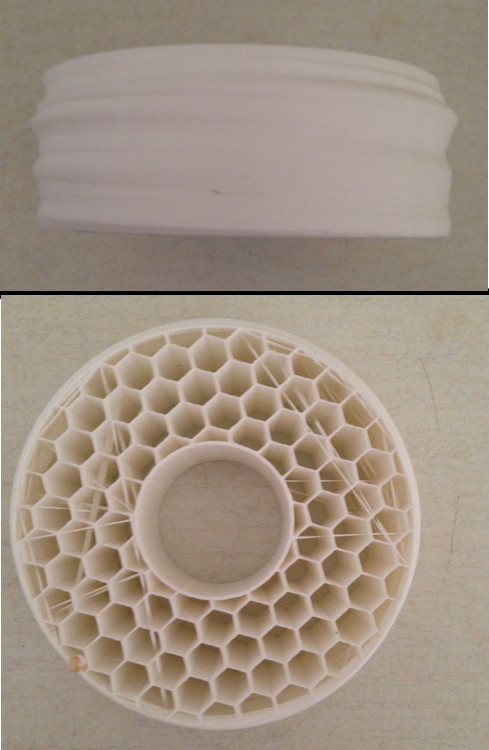

The resulting object was quite simple to print, as printing the profiles on their head easily compensated the overhangs of the noses and other facial features. I decided to use the MakerBot to print my piece, but, on the first try for which I had set my project’s diameter at 10cm, it simply (and painfully) crashed after four hours into the process. I couldn’t really pin down the source of the problem, but something as stupid as a momentaneous misconnection between the machine and the computer might very well explain the whole thing. As I couldn’t afford to monopolize the machine for another five hours, I opted for a smaller version of my project by reducing its diameter at 5cm, which divided the printing time by five. While the piece doesn’t look like much at a first glimpse, the machine’s layers of plastic quite smoothly embody the transformation from one profile to the other and stands for a promising first prototype for a potential, larger version later on.

See below for all the details/for each step.

Part II: 3D scanning

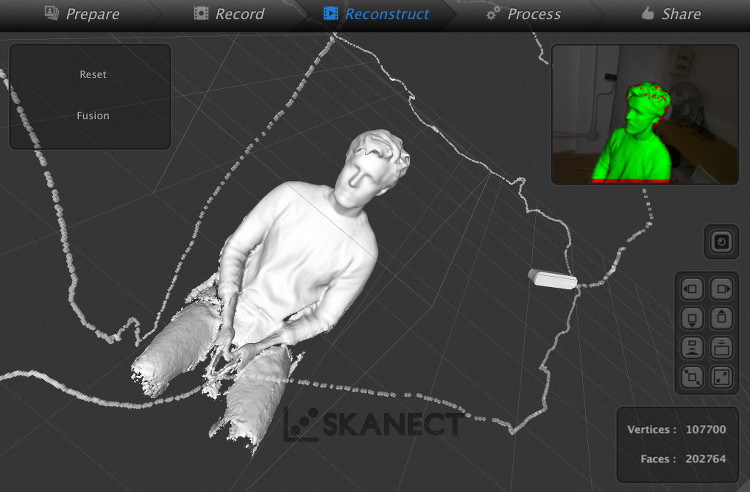

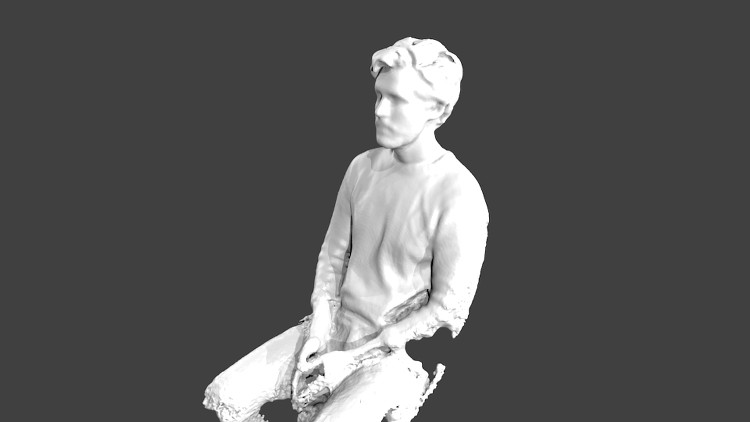

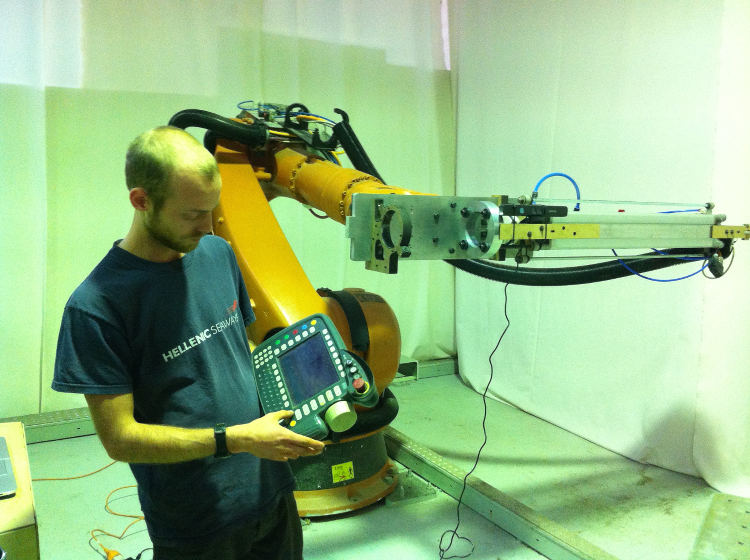

The second assignment for this week was to make a 3D scan of a person, an object or a space. Quite unoriginally, I attempted at making a 3D scan of myself, yet did so as a way to test various different technics. In the first case, I gave a try to Autodesk’s online app 123D Catch – a photogrammetric software building a model out of its subject’s photos – and, in the others, used Skanect and a Kinect to make a scan both by hand and with the end of IAAC’s 6-axis robotic arm. The result of the first try was quite catastrophic – while the software seems quite powerful, taking the right photos is extremely tricky and I couldn’t achieve the right composition to make a convincing model – but the two models I got out of Skanect were really well done and I then could try my hand at some 3D retouching using Blender.

See below for all the details/for each step.

- Week: 05

- Subject: 3D Printing & Scanning

- Tools: Rhino, Skanect, MeshLab, Blender, Maya & MakerBot

- Objective: Design and print an object that couldn't be made substractively, as well as make a 3D scan of an object.

- Files: Click here